Corinne Dedini Corinne Dedini Science provides, by definition, fact-based conclusions. But beliefs get their moments in the sun too, and are often rooted in lived experience. As a science teacher and a person of faith, I have sat in this tension all my life. And I have come to understand that science can’t answer questions of faith, nor can faith answer questions of science; the two, again by definition, are mutually exclusive. So what do you do when your beliefs - for which you may even have some anecdotal evidence - about teaching and learning aren’t supported by the science? You allow the research to challenge your assumptions. Every year we dive deep into the literature to answer tough pedagogical and curricular questions. Here are three myths that we’ve tackled over the years. Myth #1: Online learning is sterile. Research: Connection between student and teacher is the cornerstone of online learning. When the Online School for Girls started, we had to overcome a lot of assumptions, not just about online learning but also about best practices for teaching girls online. With the guidance of Lisa Damour of Laurel’s Center for Research on Girls, we built a research-based pedagogy on four pillars: connection, collaboration, creativity, and application. When it comes to student-teacher connection, the belief isn’t antithetical to the research - the more sterile the online learning environment is, the less likely students are to finish the course. So we design intentionally for the experience of connection, building video, meetings, and collaborations into each course. Ten years later, connection is still the most important piece of the user experience at One Schoolhouse: we track it quarterly in our classes, and draw a direct correlation between the experience of connectedness and our 95% course completion rate. Online learning can’t be sterile. Myth #2: Students can’t learn language online. Research: Students don’t learn language well in traditional classrooms. It turns out that America’s way of teaching a second language is an abysmal failure. The research shows that fewer than 1% of Americans are proficient in the language they studied in school. When I kept saying “no” to our schools who were asking for the full Chinese and Latin sequences online, I was holding tight to my fear that language couldn’t be taught well online. Once I discovered that there’s almost no evidence that “the way we’ve always done it” in traditional classrooms works, then I started exploring progressive practices that do work. And guess what? They all involve either intensive immersion experiences (no surprise there) or the effective use of technology that intentionally breaks the learning into the four language competencies. As a competency-based school, now we had the research to guide the building out our language program. Myth #3: Some students just can’t learn online. Research: Most students just haven’t been taught how to learn online yet. The fixed vs. growth mindset is the decisive blow to the beliefs-trump-research argument. Being open to what the research says - and allowing it to lead you to your answer - allows you to gracefully move from your fixed belief to a more expansive understanding. In this case, the research--and the experience of every teacher I know--says every student learns differently. That’s as true in the online space as it is in the brick-and-mortar classroom. Just as classroom teachers need a toolbox of approaches, well-trained online teachers have an array of strategies at their fingertips to help students who mistakenly think they can't learn online. The truth is, they just can’t do it because no one has taught them how to yet. Myth-busting research isn’t always a bird in hand, though. There are times when it is hard to find the research that answers my question exactly. We are, as the first supplemental online independent school, a pretty unique entity. No one is studying schools just like ours. But we are cautious not to dismiss research because at first glance it doesn’t seem to specifically apply to us. Often a closer study offers useful analysis that can inform our decisions. Sometimes, I realize that I’m not even asking the right question. In these cases, I have to use the data I’m finding to ask bigger, more mission-aligned questions. So the next time that you are faced with a question about teaching and learning, look to the research and allow it to challenge your assumptions. When you can’t find research that aligns with what you’re looking for, ask yourself if you’re asking the right question. Adjust your question so you can get a bird’s eye view. Your school will be better for it. Whether you are an administrator, department chair or a classroom teacher, we have research to help on your journey towards challenging assumptions and resources to help you continuously improve your practice. Check them out below:

Cohort PD Courses: Thinking about how to take your school beyond standardized advanced curriculums but don't know how to go about it? This course, facilitated by Peter Gow, will provide your school with a toolbox for developing and promoting indigenous advanced learning experiences built and designed for your own student body. Course begins April 1, 2019. Beyond: Preparing Your School for the Journey to Independent Advanced Curriculum On-Demand PD Programs: If you are looking to dive into the world of personalized learning, we offer three, four-hour long programs that give you the tools you need to begin to redesign your classroom from a learner-driven approach. Introduction to Personalized Learning: The Why, How, What Personalizing Pathways: Creating Student Voice and Choice Student Agency: The Foundation of a Learner-Driven Pedagogy White-Papers & Blogs:

0 Comments

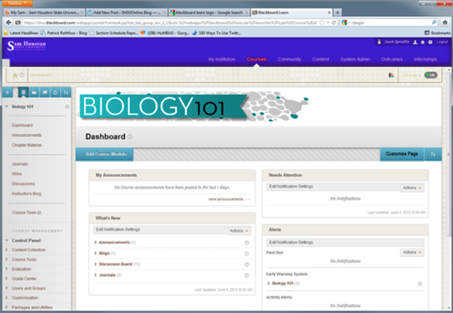

Peter Gow Peter Gow A history teacher encounters a dismissive and demeaning reference to gay and lesbian people in a student essay. A Spanish teacher senses that students are obliquely mocking stereotypes of Latinx persons during conversational practice exercises. An English student continually asserts in class discussions of a Toni Morrison novel that white people are an imperiled minority. These are teachable moments, right? The teacher must call on the students to justify their statements with facts or counterarguments, reminding them in teacherly ways that such expressions might be painful to some listeners or readers. Operating within the constraints of the “free speech rights” of the student versus the teacher’s obligation to protect fact and uphold the values of the school, the dialogue or debate must go forward, counter-argument against counter-argument, until some kind of stasis—maybe just an agreement to disagree—is reached. But when, confronted with obvious evidence, can a teacher call out behavior or expression as racist or as expressing a kind of bias that is at odds not only with the teacher’s own values but those implicit or explicit in the school’s statements of values and beliefs? Is this ever the right thing to do, and can a teacher reasonably expect that a school administration will back them up? And it’s not just students, we know. A faculty member might hold and express biased perspectives on certain groups of people, subtly and infrequently expressed well beyond the sight or earshot of students, but nonetheless painful to colleagues. It’s easy for schools to address anonymous or flagrant bias incidents: the note on the locker, the social media post, the abhorrent photograph. The leadership appropriately musters the community’s righteous indignation, reminds everyone that there is no place for this kind of thing, and perhaps even separates members caught red-handed in behavior that is patently and intentionally hurtful to others. All this is as easy as expelling the students caught vaping in a bathroom where This Is A Non-Smoking Campus. But let’s say that a student or students are well known in the community for living in a household where prejudiced perspectives are the norm. Either because the school didn’t know about or ignored these oppositional values during the admission process or because the household in question has some authority in or special value to the school as an institution, the children of the household arrive at school each day armed with beliefs that might be inflammatory but shielded from the consequences of expressing these beliefs by their special privilege. To confront these students of “parents of power,” as I call them, is to risk one’s job, and every private school teacher knows it. We exhort independent schools, in particular, to live by their missions and values, to build their communities and cultures of learning around high ideals embodied in lofty mission statements and positive assertions. In our most optimistic moments we can imagine that these statements and the supporting evidence schools provide in their marketing and advancement messaging comprise a covenant between schools and families: a solemn, high-stakes promise made and to be kept by the school. But in whose name do we create these aspirational statements? Is it for the institution as a corporate entity, a “we” that offers a side-door out through which contrary-minded individuals, in the moment or in their own committed beliefs, can usher themselves without consequence? Or are these aspirational statements of values and purposes (or should they be) intended as benign but rock-hard imperatives that serve as the moral and ethical foundation of intentional communities? Does your school’s enrollment contract explicitly connect supporting your school’s mission and values to community membership? Does your board’s “Statement on Diversity” (perhaps now looking a bit long in the tooth, as many of these are) commit not just the institution but its members—faculty, students, and families alike—to abiding by its expressed principles of equity and inclusion? In other words, do or should school’s statements of values and purposes have any teeth? Can a student be confronted not just with the illogic of a biased position but with the ways such positions clash with and undermine the ideals of the community? Can students and families legitimately be asked to check protective privilege at the schoolhouse door as antithetical to stated ideals around diversity, equity, and inclusion? Might offended and uncomfortable teachers reasonably expect that, beyond having to make their personal case to individual students against hurtful or hateful expressions, their schools will support them by addressing these expressions not just as classroom issues but as institutional ones? No school, of course, can address such questions to any positive effect in the absence of its own community understandings of norms and values around DEI issues. No student can be meaningfully confronted about hurtful expression if the school has not engaged in community-wide conversations and professional learning that provide tools and language for discussing these issues. If the school has an office charged with oversight of such conversations and learning, so much the better, but the work must be everyone’s. No effective remonstrance can be issued in the absence of a palpable sense that certain affirmative values are the way “we”—the institution and its individual members—are and must expect themselves to be. Schools must truly live by the courage of their convictions. If such things matter to a school as much as most schools say they do, the school must be committed to calling out—and perhaps calling the question on—expression that violates its stated ideals. When teachable moments in a classroom don’t or can’t teach, the institution and all that it stands for must be prepared and willing to step up and step in.  Brad Rathgeber Brad Rathgeber When we talked about starting an independent school online, our colleagues at our schools looked at us as if we were crazy. In those days, people in our communities assumed that online learning was everything our schools were not: rote, lonely, boring, easy. When we looked online, we saw the potential for online learning to be so much more: connected, challenging, engaging. The truth is, in 2009, most online courses were focused on content and rote learning, as you might be able to see from this screenshot from a college course in the same year. But, in 2009, more and more social media tools (what we used to call “web 2.0” tools) were coming online. The internet became about connection, rather than giving knowledge. And, the tools for connection were becoming affordable in a way that they never were before. This new way of using the internet allowed for a new way to teach online. So, we enlisted the help of our friends at the Laurel School’s Center for Research on Girls, and their exceptional leader, Lisa Damour. The Center scoured research available to create a pedagogical approach for teaching and learning online that was relational, developing four pillars for girls’ learning online:

Thus, connection, collaboration, creativity, and application became the cornerstone of our work with students online, giving us the basis for challenging the assumption that learning online could not be exceptional and relational. And now, 10 year later, what do we know about at our courses? Well, 97% of our students say that their One Schoolhouse courses are as challenging or more challenging than their face-to-face classes, 82% report gaining greater academic maturity, 77% report being inspired to be creative, and 85% report seeing direct ties between classroom learning and real-world application. We make progress on each of these fronts every year, continuously going back to the research to update our practice, staying true to our roots of being research driven in order to create something beyond expectation. I’ll write about that part of the journey next month - Design Backwards, Then Measure. |

Don't miss our weekly blog posts by joining our newsletter mailing list below:AuthorsBrad Rathgeber (he/him/his) Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed