Peter Gow Peter Gow It’s summer, when many Americans are privileged to head off to visit family and old home towns or to sojourn a while among woods, water, mountains, or even deserts, happy for a few days or weeks or even months to immerse themselves in what they might even call their “happy place.” Many of us can tell of important life lessons learned when we’ve been able to connect deeply with a particular place, and some folks become very, very deeply invested in the spirit and history of their special corner of the world. As we emerge from our pandemic hidey holes back into all the parts of the world we love and take up travel once again, we urge our educator friends and family to consider how these relationships with places—all kinds of places— might be harnessed as engines for teaching and learning. There’s nothing terribly new here. “Place-Based Learning”—I like to call it PlaBL to differentiate it from the other Ps (PjBL for projects and PbBL for problems)—has been around for a while, and a few schools have really capitalized on their own locations to build academic programs around the mountains or waters near which they are situated. Some have even gone further. Our friends at University Liggett School near Detroit, Michigan, have created a truly exemplary United States History course that takes students through time through the lens of the history of its own region. Some years ago I had the good luck to have been approached by a couple of students who wanted to do an independent study, and our exploratory conversations led us to their interest in the history of their own small city. Voila! “Newton in the Revolutionary Era” was followed by “Newton in the Civil War Era,” and some interesting learning took place. Later I had a side-gig as an editor for a small regional press, and in my mind I began to translate Tip O’Neill’s maxim about politics into my own mantra: “All history is local history.” But that’s just one discipline. Plenty of important place-based learning has been done around the sciences, data-collection, and quantitative analysis. Multilingual communities and regions abound. One could argue that many of the fine arts and much literature are place-inspired, and few places are without their “local” authors and artists of note. The possibilities expand far beyond traditional academics. Local advocacy and community engagement can have transformative effects on both places and people, and I’ve even worked with one place-named school that had taken on the challenge of being THAT PLACE’s Academy, finding ways to make the school’s and its students’ presence in the community positive forces, rather than just being another aloof School On A Hill. Place-Based Learning connects students intellectually as well as emotionally to their communities and their natural environments, opening windows into history, culture, geography, politics, and current issues of equity and justice—all the ways that “place” can inspire art and beauty or serve as a kind of trap for humans and our fellow creatures. If we are seeking learning that is “relevant”—that acknowledges that students’ lives are actually being lived somewhere and that deeper understanding and responsible and equitable stewardship of these places is a human imperative—you cannot do much better than embracing PlaBL in its full expression. Like PbBL and PjBL, Place-Based Learning can free and inspire teachers and students alike to begin seeing communities and localities as classrooms, laboratories of the human experience that inspire important questions and take us on journeys toward answers whose complexity and significance transcend textbook algorithms and received truths. I believe that all three Ps—Place-, Problem-, and Project-Based Learning—are worthy of increased attention. As we become more sophisticated and creative in our independent approaches to curriculum and assessment and as we understand more deeply the role of personal experience in students’ development as learners, we cannot overestimate the possibilities of Place-Based Learning and its cousins as effective learning tools that help students understand that their place in the world is an actual place, in an actual world.

0 Comments

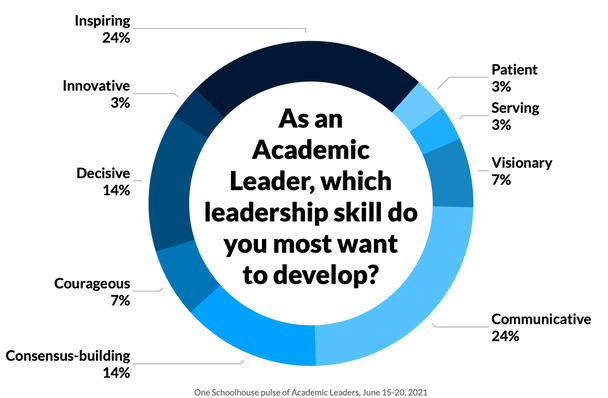

Each week One Schoolhouse offers a “Pulse Survey” on a topic of relevance to our work as educators. Last week’s question was, “As an academic leader, what leadership skills do you most want to develop?” Participants were asked to pick one from a menu of choices. Any survey reveals more than numbers, and this one was illuminating and not a little puzzling to your authors, suggesting patterns in conceptions of skillful leadership that leave difficult questions either unanswered or answered in worrisome ways. “Communicative” and “Inspiring” led the responses, with “Consensus Building” and “Decisive” making a kind of odd couple in second place. Bronze went to “Courageous” and “Visionary,” with “Patient,” “Serving,” and “Innovative” bringing up the rear. But your authors were struck by some entry choices that were completely unchosen. One can rationalize why these options might have been unpopular, but their omission might also point elsewhere. We can grant that “Empathetic,” “Flexible,” and even “Stable” might be worn out after the emotional roller-coaster of being an academic leader in the pandemic. But, we do wonder. And the absence of “Equitable” and “Inclusive” has us utterly stumped. The unchosen responses that struck us hardest, however, were “Honest” and “Accountable.” We see honesty and accountability as two sides of the same coin, where one cannot truly exist without the other. Is everyone already prepared, so confident in the overall integrity and efficacy of their work in their institution, to take on difficult conversations about difficult topics, to confront hard things with courage, moral certainty, and an honest willingness to own the challenges and the failures? Are we finished with this work? If we’re not, shouldn’t that mean that honesty and accountability remain as major areas for work—not just on one’s personal leaderly chops but on how one’s school fosters an ethical culture and accountability to its own constituencies? In all the work of schools, most critically in the areas of diversity, equity, inclusion, belonging, and social justice, accountability must come first. We must acknowledge and hold ourselves accountable for the hard reality that systemic biases differentiate the experiences of members of marginalized groups in our communities from those of students and staff who are members of traditionally privileged groups. Academic leaders must be accountable themselves and create pathways for their institutions to hold themselves accountable. A readiness to do the difficult work well begins with a willingness to own accountability not just for what is but for our successes and our failures on the journey forward. There are mountains to be climbed, but we have to crawl and then walk up to and through our challenges—in our situations and in ourselves—before we can begin the long, hard run to the problem-solving pinnacles to which we aspire. Leaders are exhausted, yes, but we must sustain our personal and institutional climbs to the mountaintop, no matter how tired we may be or how determined the resistance we encounter. It will be schools’ successes in these areas that can inspire and bring together our communities and hopefully our world, making the most commonly cited areas for work noted in our survey happy by-products of accountability and honesty. In many indigenous communities, leadership is recognized as something that is earned, and here are ways in which aspiring leaders can demonstrate their worth. We know. It was just a quick survey, and people are busy. But of late we have heard so much from schools and educators eager to take on systemic inequities and other challenges in their schools and curricula, and as an industry we have ballyhooed our commitment to these battles. We must fight them as hard and honestly as we can and accept the fruits of our labors. We feel every day the overwhelming tide of good intentions within our community of educators, and we call upon each of us—not excepting ourselves, believe us—to double down on making our schools not just programmatically but ethically worthy of our independence. The future will hold us accountable. But so must we ourselves, starting now.  Sarah Hanawald Sarah Hanawald Narratives have the power to move people and motivate change. We’ve seen this time and again. Although we value the storyteller and share their videos or written words far and wide, we sometimes forget that all narratives are created by data--if we expand our definition of what data can be. When we consider “data” in independent schools, we often envision a complex database, a spreadsheet download, or an enormous file that has to be read, digested, and massaged into a presentation. That may be true of quantitative data, but qualitative data is collated and created every day. I recently had the chance to have a conversation with Joel Sohn, the Upper School Director at University Prep in Seattle. Joel has a unique lens. In his work, he describes looking for the data story. In fact, his hunt for data begins with building relationships. Joel knew that various campus offices had information he could use to help lead DEIB initiatives. He also knew that just saying “give me access to your files” wouldn’t get him far. Instead, Joel sought to build relationships with individuals across campus, admissions, student life, libraries and more. He knew that all of them had smaller data sets that represent specific campus functions or constituent groups. The goal with this building relationships was to help colleagues understand that his goals were to improve the institution, not looking for a “gotcha.” Once the trust was established; peer leaders on campus became co-researchers. For example student life had data on when students took leaves of absence or left campus early. Was there something to be learned about how that data merged with other information about students? Did students with a particular identity miss school during times that led to a greater impact on grades? Only with the right information could the story emerge that could inspire school leaders to improve the stories that needed to change, and celebrate those that were newly discovered. What emerged during my conversation with Joel was his discovery that sometimes qualitative data can be the more powerful source of initiating and leading change. A spreadsheet full of numbers can feel distant from lived experiences, but the story of an individual student has the power to move people to understand that the need for change is urgent and requires action. What data stories are there, hidden at your school, waiting for you and your colleagues to find and share?  Lorri Palko Lorri Palko This past year, Lorri Palko has taught several sections of One Schoolhouse’s online course, Building Trust With Faculty. In this course, Lorri advises leaders on how to build professional relationships that support healthy communities of trust. As she prepares to teach the summer sessions of the course, Lorri talked to Sarah Hanawald, One Schoolhouse’s Assistant Head for Professional Development and New Programs, to reflect on what she’s discovered about independent school leadership in the past year. Academic Leaders have been under tremendous pressure for the entire year. They felt like they needed to perceive what needed to be done, make a judgment call on the action to be taken, and follow through accordingly--and to do all this quickly. This year, there were so many issues that school leaders had to react to and act on quickly that they didn’t realize their fast actions had imperiled some of their relationships with teachers on campus. In a lot of cases, that happened because leaders didn’t have empathy skills that were adequate for the challenges they faced. Let me be clear--these are kind, caring individuals. Academic Leaders are drawn to their work because they care intensely about their communities and the people in them. But empathy doesn’t mean being understanding and warmhearted. Empathy is our ability to understand what someone else is experiencing, and to put aside our own judgment and perspective. When leaders move fast, especially under stress, it’s all too easy to overlook the way that our unconscious biases and beliefs can get in the way of our ability to really see things from someone else’s perspective. One challenge for leaders was that many fell into the trap of listening to others with what I call a “Me Focus.” With this focus, the listener isn’t seeking to understand, but is instead focused on their own thoughts, feelings, and judgments. This leads to statements like “I know just how you feel.” The listener thinks they’re making a connection, but the speaker feels unrecognized and unvalued. Another missed opportunity to build trust is when leaders view a conversation as a problem to be solved rather than an authentic connection with another person. If a leader is focused on constructing a response, they’re not really listening to what the other person is saying. Shifting that focus to asking questions and following another’s lead is what it takes to begin to build empathy. Effective leaders cultivate self-awareness. Self-awareness is the gateway to being a leader who inspires trust and confidence from others. We cultivate self-awareness by allowing ourselves to recognize and name our emotions. Self-awareness allows us to quiet the inner critic who says, “You’re not good enough, you can’t do this.” When we save space and time for wisdom and intuition to come forward, we give ourselves permission to choose a higher thought and take inspired action. Self-awareness allows us to access the highest expression of empathetic conversation, which is holistic listening, when you use all your senses and your intuition to truly understand what the other person may be saying, or not saying, but still revealing. When leaders are self-aware, they can bring all of themselves to a conversation--and they can recognize, acknowledge, and honor the complexity and vulnerability of another person’s experience. When a leader can listen this way, then real professional trust can be earned and rebuilt. Join Lorri for Building Trust With Faculty June 14 - 25, 2021 or July 12 - 23, and learn how to better support teachers who are facing change, disruption, or challenges professionally and in their lives. Participants will learn how to lead affirming coaching conversations that foster healthy, trusting relationships, so that the resulting professional culture provides support for faculty members that mirrors the schools’ concern for and support of students.  Brad Rathgeber Brad Rathgeber On behalf of the 2020-21 One Schoolhouse Board of Trustees, it is my honor and privilege to congratulate and thank Brad Rathgeber, co-founder and original board president of Online School for Girls, and current head of school and CEO of One Schoolhouse, for 10 years of extraordinary executive leadership of this dynamic educational organization. In the winter of 2009, four independent girls’ schools – Harpeth Hall School (TN), Holton-Arms School (MD), Laurel School (OH) and Westover School (CT) – formed a non-profit consortium to become the world’s first online single-sex school and the first online independent school: the Online School for Girls (OSG). They came together with common beliefs that online education was an increasingly powerful way to learn, and that there was great value in creating an online learning environment built on the traditions of independent schools and girls' schools. Their foresight has proven to be incredibly accurate.

Brad and his colleagues have created a unique supplemental educational organization that provides courses and programs for students and adult learners across our independent school community and across the globe. A smart business model and affordable pricing has allowed all types and sizes of schools, and even individual students, to benefit from One Schoolhouse’s programming. As a result, hundreds of schools and thousands of students benefit from Brad’s leadership annually. Via One Schoolhouse's mission to empower learning and transform education, he has helped numerous schools and associations solve problems and transform their delivery channels. This recognition for Brad in June 2021 is extremely timely because of his leadership as One Schoolhouse pivoted to support schools through the COVID-19 pandemic as they transitioned to remote instruction. He and his team provided advice, guidance, training, tools and resources every step of the way. As a result of their impact, thousands of educators were better prepared to provide quality remote and hybrid learning experiences this past fall. During his tenure, Brad has also represented himself and One Schoolhouse with great aplomb through his service on the board of the National Business Officers Association (NBOA), 2012-2018; National Coalition of Girls’ Schools (NCGS), 2013-2019; NCAA’s High School Review Committee, 2013-2020; and Educational Records Bureau (ERB), 2019 – Present. In addition, he is a regular contributor to NAIS’ Independent School Magazine, NBOA’s Net Assets magazine and other professional publications. And he is visible at educational conferences and meetings across the country, learning, growing, and sharing industry expertise. We thank Brad for his service to One Schoolhouse, for his stellar leadership of an innovative and impressive leadership team and faculty, for his contributions to the entire PK-12 independent school community and most of all, for his friendship and collegiality. With gratitude and admiration, James R. Palmieri, Ed.D. Board President, One Schoolhouse Executive Vice President, NBOA Comments from prior Board Presidents:

From Kathryn Purcell, One Schoolhouse board president 2017-2020: “Working with Brad has been an incredible professional and personal experience – one that allowed me to grow and learn as much as to serve One Schoolhouse. Brad is a consummate educator and professional. He is both visionary and incredibly adept at management and operations. He is always ahead of the curve, looking beyond the horizon, and fearless about taking on challenge. One Schoolhouse has thrived under his able leadership, and for that, we are immeasurably grateful. “ From Cathy Murphree, Online School for Girls board president 2012-2017: “Brad is a multi-talented leader-visionary, master communicator, relationship-builder, networker, effective team leader – and his positive energy is unsurpassed! One Schoolhouse has been so fortunate to have Brad at the helm; independent schools, teachers and most importantly students have all benefited from Brad’s OSG/One Schoolhouse leadership.” From Karen Douse, Online School for Girls board president 2011-2012: “I succeeded Brad as board chair when he was hired as OSG’s Head of School. Brad’s greatest gift, then and now, has been his strong vision for the role of online education in the future. It is that unwavering vision that has resulted in the success of One Schoolhouse today.” |

Don't miss our weekly blog posts by joining our newsletter mailing list below:AuthorsBrad Rathgeber (he/him/his) Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed