Corinne Dedini Corinne Dedini I spent a good decade of my career differentiating instruction for students with learning differences. Drawing on the wealth of research, I dutifully created lessons with a range of learning modalities and designed units where all students had at least a few activities that suited them best. I’ll bet every teacher has done something similar. Here’s why this isn’t the best approach: every student learns differently so differentiated instruction is highly inefficient. We all know the problem with differentiation: all students -- regardless of whether they have a diagnosed learning difference or not -- still have to do a lot of activities that don’t all meet their needs, and the teacher exhausts herself to create a range of activities in the hope that there will be something for everyone. But in reality, every student is unique. Even creating a robust station rotation won’t enable a teacher to meet every single student’s needs. Differentiation is a recipe for both student and teacher fatigue. This challenge is exacerbated by the reality that sometimes what we label as “learning styles” are not even innate, but are actually learned survival tools. Lisa Damour, in her new book Under Pressure, describes a student making 50 flashcards for a test when she actually only has 10 words she doesn’t know; still, she reviews all 50 repeatedly because this is how she has learned to do school and because it earns teacher praise. (This example gets even more frustrating when you consider the research on the relative uselessness of flashcards in general!) There’s nothing innate about flashcard studying. What is actually innate is the way we are hardwired to learn most effectively and efficiently; for most, it isn’t flashcards, but in a differentiated model, we honor difference by teaching every student to use every tool, regardless of usefulness to their unique learning needs. While well intended, ineffective activities (i.e.: flashcards) are compounded by the inefficiency of the learning routine in the differentiated classroom. Some students need to read an overview to understand the context of a new skill, while others are better served by diving right into an activity and then learning the skill by trying it out, failing, and trying again. Why should the student who likes to read or study first and then do problems have to do 20 problems to show she knows the new skill? After reading and studying, maybe she can show mastery with just five problems. And why should the student who would rather work through a problem set -- getting it wrong and reverse engineering the answer until she masters the skill -- have to read the chapter in the book before starting the problems? Because, as dutiful differentiators, we do all things for all students and in return we ask all students to do all things we’ve designed. The good news is that it doesn’t have to be this way. Teachers can create pathways where students access new content and skills in the way that is most effective and efficient for them. And a side benefit of these personalized pathways is that all those differentiated lessons transition nicely to optional pathways in a personalized paradigm, so this will be a housecleaning exercise for teachers making the shift. Learning Pathways -- where teachers design alternative pathways for efficiency, acceleration, and remediation -- motivate learners because they prevent stagnation, plug holes, and minimize inefficiencies. They do this by giving students choice in what they learn and by inviting student voice into how they learn. (It’s not as scary as it sounds.) This keeps students engaged in their learning, ultimately increasing mastery, because they aren’t wasting time on things that don’t help them learn. Pathways allow teachers to meet a range of learner needs because they give students multiple onramps to new content and skills. Any teacher with some basic edtech knowledge and access to the Google Suite or a LMS can create personalized pathways that leverage all the tools that the teacher has in her differentiation toolbox to make the students do meaningful, useful work via learning pathways. Want to try it out? Take a stale lesson, write every single activity on a separate sticky note, stack the sticky notes that essentially accomplish the same things (for example, listening to the lecture and reading the textbook), and let students choose just one activity from each of the stacks. By personalizing instead of differentiating, you’ll gain 30 minutes here, 45 minutes there -- for you and for the students -- that you can now reallocate! The first time you do it, use that time you gained to ask the students to share their thoughts on the change. Differentiation had its place - it taught us to recognize that all students learn differently, and it helped us move away from the sage on the stage model. But it’s time to move on from differentiated instruction. When you stop differentiating and start creating personalized pathways for learning, you will infuse new life into your curriculum.

0 Comments

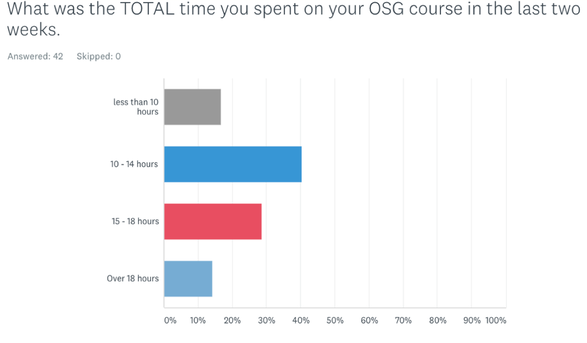

Brad Rathgeber Brad Rathgeber Looking back on the last ten years, it is easy to reflect on how much we learned early on. We learned what works well online and what doesn’t. We learned that meaningful connections between students and teachers and students with each other was possible. We also learned that there were some significant differences between the online and face-to-face learning spaces — ones that created advantages for the face-to-face classroom, and, yes, ones that created advantages for the online classroom, too. The first advantage that we found was data was plentiful in the online learning environment. We knew where students were clicking, and how they were progressing through their work. Student learning and process was more transparent. We also deliberately asked for student perceptions on their learning — regularly, and at least quarterly, as mentioned last month. Data should help you ask good questions. And, in our case, one of the first questions came in regards to an assumption that we made about time spent in online classes. The chart above is from our student survey in October 2010. We asked students how much time they had spent in their online course in the previous two weeks. We were hoping to see alignment between student time and the expectations we had set with faculty (that coursework take approximately 7-8 hours per week or 14-16 hours over a two week span). Certainly, much of what students reported was in line with this expectation. But, much of it wasn’t too… About 30% of students reported spending either less than 10 hours or more than 18 hours in their online course. We were expecting almost all students to be in one of two categories… what we got was a quick lesson that (duh!) students learn at different paces. When we dug deeper, we realized that there was no real connection between time spent and grades achieved either. That helped us come to an understanding that became an advantage of the online learning space: time was more flexible than in the classroom learning space. We learned about other advantages of learning online early on, too. This is Erissa, then a sophomore at Harpeth Hall School in Nashville. Erissa enrolled in one of our first Alpha test classes, Genetics. In late fall 2009, I travelled to Nashville with Erissa’s teacher to have conversations with administrators at Harpeth Hall, and understand their impressions of the test courses.

When we sat down with the Upper School Director, Erissa’s teacher noted how exceptional she was, telling the administrator that Erissa was the leader of her class, and that she was particularly impressive as a sophomore in a class where all other students were juniors and seniors. The Harpeth administrator thought we were mistaken: “You must be talking about Katherine or Julie?” No… we were sure, Erissa was the leader. “Erissa never says a word in class,” the administrator told us. This was our first of many lessons that the online learning space was particularly good for introverted students. Online learning spaces offered time for reflection, and for students to engage when they were ready to, instead of when the teacher wanted them to. Erissa had the time and space to reflect and engage on her terms, and thus blossomed as a leader. We’ve continued to learn and grow over the years, as we’ve reached more and different types of students -- from younger learners, to students with learning differences, to boys (yes, we did start without an all-gender division), etc.. This month, you’ll continue to hear our lessons in this regard, and learn where we’re going to continue to grow. |

Don't miss our weekly blog posts by joining our newsletter mailing list below:AuthorsBrad Rathgeber (he/him/his) Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed