Peter Gow Peter Gow When I was in college I envied friends at colleges with “Jan Terms.” From my vantage point at a ponderous, grad school-ridden university, these four-week terms looked pretty appealing, great examples of nimble, student-interested-based programs that could happen in smaller liberal arts colleges to make education fresh and exciting. Jan Terms, or mini-terms of any sort, were what could happen in colleges where students knew where their professors lived in the town and could run into them, with their families, at the store. They were times when students and faculty could embark on intensive explorations of shared passions in an immersive spirit of fellowship and relatively low stakes. At the college level and among those secondary schools that also adopted the practice, mini-terms pretty much went the way of the dodo as education shook off the impulses of the Seventies and became more “serious.” In a few places they held on and even remained beloved and important segments of the academic program, but for the most part the weight of “coverage” and its evil twin, standardized testing, drove idiosyncratic approaches to learning out of the students’ high school programs, at least until senior year and electives after the pressures of SAT Subject Test and at least some AP exams have passed. But the mini-term is having something of a revival, with more and more schools expressing interest and making inquiries on various listservs and Twitter chats. There seems to be some interest in breaking up the calendar to make space for deeper explorations of single topics or approaches. I think I know why this is, and I am very much of two minds about it—not approval and disapproval, but rather strong approval and a sort of dismay tempered by optimism. In the last few years there has been a revival, or an enthusiastic reappraisal, of the idea of “project-based learning,” especially in the form of design thinking. Great projects, and really deep design thinking, are, like the old Jan Terms, immersive experiences, hard to chop up into 55- or 70-minute chunks distributed throughout a week. Ideally these are undertaken full time, and often they are accompanied by an element of “making” that requires its own commitment of time to design, prototype, and improve. There is enormous peer pressure these days on schools, especially independent schools, to embrace “PBL” (which I prefer to call “PjBL” to distinguish it from Problem-Based Learning, which I learned as a structured case-study-like approach to analysis and which often is lumped, confusingly, under the PBL tag with its project-based cousin), “maker culture,” and design thinking. Oftentimes the umbrella under which these fall also shelters STEM and STEAM as well as some of our other enthusiasms of the moment: entrepreneurship, global education, community engagement…. In the listserv queries about mini-terms one can hear the echoes of the central question at curriculum committee meetings in which these new concepts are being discussed: How is a school supposed to incorporate these amorphous, insistently good ideas into a curriculum rigidly segmented by discipline and already tidily packed and parceled into daily doses? If we must sacrifice coverage, how best to do this without inconveniencing or riling up anxious faculty? The frequent answer, of course, is to peel out two or three weeks in which the school can devote most of the academic days to this kind of “non-traditional” (and what I bet some really cynical teachers call “non-academic”) work. Crank up the design lab, clear the maker space, and lay in pounds of new filament for the 3-D printer! Sign the kids up for the “global education” trip to Belgium or Costa Rica! Prepare for the internship project with our sister school in the urban core! The school has figured out how to make time for these self-evidently worthy enterprises without totally exploding the curriculum or the schedule; maybe language classes even run as usual, an hour of normalcy in what are otherwise days of unfamiliar openness and energy focused on goals less clear and concrete than reading Chapter 16 or diagramming the Krebs Cycle. Often enough, the mini-term takes place when educators allow themselves to subscribe to the convenient fiction that “you can’t really get anything done, then, anyhow”: the interval between Thanksgiving and December breaks, the last weeks of May, the weeks just preceding spring break. We surrender to the basement-level expectation that these periods are “write-offs” anyway, although of course they should not and do not have to be. Check the timing, if you don’t believe me, of the national “Hour of Code,” another brief and highly worthy excursion away from the traditional and into the future. As great as these programs and ideas are, however, there’s something a little disheartening about the resurgence of mini-terms. They are at least partly an admission that project-based learning, design thinking, global education, coding, and the rest are simply too hard to incorporate into the life and work of the “regular” classroom, that their principles are, for the moment, too difficult for teachers to grasp and adapt into their daily practice. Well, everything has to start somewhere. I happen to have worked for many years in a school that has made a practice of figuring out ways to incorporate good ideas “across the curriculum,” most recently and famously computer programming. The faculty are enthusiastic early adopters who, by intentional hiring and frequent training, tend not to be overwhelmed by trying to figure out how to make social justice a part of Algebra II or design thinking a part of tenth-grade English. It’s a pretty great model and a fascinating place to work, but it’s not a model that can be bottled for instant consumption by every school. But the mini-term, I like to think, is a great first step for schools. In my perfect world, mini-terms open the door to a sea-change in the way schools do their work. They are test beds for innovative(!) practices that will soon wriggle their way into those 55-minute lessons and even start breaking down barriers between disciplines. In time, the new methods and approaches of mini-terms may unseat King Coverage and lead the way toward the reign of skills and habits of mind (or mindsets, if you will) as the central subject of educators’ work. Real (if rare) experience says that you can actually teach project-based Algebra II or design thinking-informed Honors English or even global-aware Chemistry, once you have internalized the methods and the goals and freed yourself from the domination of “coverage.” Thus, my hope is that each school now contemplating or embarking on a mini-term system has in mind the larger goal of making the themes and methods of these short-term “events” integral parts of its institutional methods and permanent academic culture. If mini-terms must have a revival, let them absolutely not be a place to which good ideas and exciting, engaging practices are relegated in order to preserve the same-old, same-old.

0 Comments

Corinne Dedini Corinne Dedini In the last 10 years, we have harnessed the research on and witnessed for ourselves the powerful connection between student agency and motivation. When students are given the ability to make small choices around how and what they learn, their engagement with the course changes in a range of positive ways. We see students work more efficiently, be driven to perform to the best of their abilities, and find space for creative exploration or time to foster a tangential curiosity. Quite simply, when students have choice, they do better across a range of success metrics. Armed with this awareness, how do we leverage choice to inspire learning and growth? There are two primary ways that we work to increase choice for students: within the class itself, as Brad wrote about earlier this month, and within the curriculum as a whole. One Schoolhouse builds courses and programs based on the needs of consortium schools. Increasingly, this has meant schools asking us to extend their course catalog via advanced semester electives, in order to give students more choices in what they can pursue, including topics like business and economics, civics and politics, computer science, engineering, gender identity, global health, neuroscience, psychology, social entrepreneurship. As we build more elective options, we wanted to go an additional step further in relation to choice, and to make courses even lower risk on the all-precious “time-consumption” meter. Our fall semester courses are interactive survey courses where students get a sense of the subject by exploring via project-based learning and case studies. For some students, this is all they want - an engaging single semester experience with a college-level topic; for others, they then want to do something with what they’ve learned in the fall. Enter a second level of choice: to stay for the second semester or to ease into spring with a lighter load (a choice we are happy to encourage for some seniors!). If they choose to stay on, they enter seminar tracks where they get to research a challenging question or design and build something that solves a real world problem. The structured deadlines of the spring seminar, combined with the flexibility pathways for deep learning, create a learning environment borne of the intersection between student agency and motivation. Students and families get more from your school when they feel like you have the choices that they want; and we’re working hard to respond to your requests for more choice in advanced electives. This post first appeared on my personal blog in July of 2017. As we enter the season of the United States’s Thanksgiving Holiday, fraught as it is with historical complexities and received narratives for which the term “bogus” can seem inadequate, we wish to present the issue and the concept of “acknowledgments of traditional land” to our community. The post has been edited slightly from the original. Regular users of this site will note that we have included our own draft land acknowledgment statement on these pages for some time. —Peter Gow, Independent Curriculum Resource Director, One Schoolhouse  Peter Gow Peter Gow “I (we) wish to acknowledge this land on which the University of Toronto operates. For thousands of years it has been the traditional land of the Huron-Wendat, the Seneca, and most recently, the Mississaugas of the Credit River. Today, this meeting place is still the home to many Indigenous people from across Turtle Island and we are grateful to have the opportunity to work on this land.” This invocation, known officially as the “Statement of Acknowledgement of Traditional Land“ (the Canadian spelling is the University of Toronto’s), begins every official function at the university. Developed “in consultation with First Nations House and its Elders Circle, some scholars in the field, and senior University officials,” the statement grows out of truth and reconciliation efforts across Canada, and it is apparently only one example of a growing genre. I’ve occasionally written about the heritage issues that might trouble the sleep of many independent schools. Creatures of their times and places, schools have not been immune to the influences of racism, sexism, and religious prejudice that shaped and continue to pollute North American society. But few schools have taken a look at the very land on which they sit—land whose history prior to European colonization is sometimes obscure but almost never unknowable. As any school that has found itself on the losing end of an eminent domain decision knows, land “ownership” is never pure and seldom simple; multiple jurisdictions (village, town, county, state, nation) have potential legal claims, for example, upon the land where sits the house that I like to think that I own. But before there were Norfolk County and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, there were millennia of native peoples with their own complex social, cultural, and political histories, and being reminded of this enriches my appreciation for those histories. It also deepens my uncomfortable understanding of the ways in which these lands became owned by white European settlers and strengthens my desire and will not to be part of oppression in my own time. It happens that one of my kids is working on a doctorate at Toronto, focusing on literatures of oppressed and underrepresented cultures, largely in diaspora. He told me about the university’s statement during a conversation about “Pocahontas deniers”—an apparently real slice of our population who apparently don’t believe or will not acknowledge that Native Americans ever existed, or even that indigenous people exist in North America today. I want to deny these deniers, but apparently they are out there, like so many other deniers of one sort or another, haughty and increasingly dangerous in their willful ignorance. So why don’t all our institutions have their own statements of acknowledgment of “Traditional Land”? You might call such a notion fussily politically correct, but schools, at least, have a purpose to be purveyors of truth, especially about themselves. What good might come of making the effort to trace the past possessors and users of the land before it became the farm or estate or other disused institution where now lies your school? What good might there be in exploring and promoting an understanding of “Turtle Island” as a construct that predates (and interrogates in a powerful way) “manifest destiny”? What good might come of creating a course or a club or a committee of students who might reach out to build connections with the contemporary indigenous neighbors and cultural bodies that exist everywhere in North America? What benefit might there be in refuting the deniers and those who believe or have been taught, as I sort of was more than a half-century ago, that Native Peoples mostly bowed off history’s stage at roughly the beginning of the 20th century—casino gambling, Western movies, and photogenic rituals notwithstanding? There are readers who will say this seems like a small and trivial point to be making against the backdrop of all the work we have to do as educators. But this concept aligns not just with general educational ideals about light and truth but also aligns quite specifically with, say, the Principles of Independent Curriculum: “Congruent with the mission and values of the school;” “High intellectual and ethical standards;” and “Inclusive and just.” It even requires the creation of understood connections between “history” and the real lives and real school work and play spaces of students and teachers—the New Relevance, of which I have written elsewhere, made manifest. As colleges struggle publicly and privately with legacies of slavery and racism, a great many independent schools these days are facing their own obligation to “truth and reconciliation” around past issues of abuse. Truth will out, it seems, so why not look at every aspect of one’s history that might need some explaining and some reconciliation? I believe that sooner or later, like colleges, schools are going to have to face even more troubling aspects of their own histories. We have shied away so far, perhaps in the belief that these things are not for children, but it strikes me that developing a statement around the very land a school occupies might be a good place to start. It’s a way to send a message that we are really prepared to talk about—and do something about—the hard stuff. So come on, schools! Step up to the plate of truth and reconciliation. If we have anything to be thankful for in 2019, it is the persistence of truth, and our task as educators is to be its champion, even when it hurts. Beth Teske, Assistant Head for Academics at Linden Hall, on how One Schoolhouse's pedagogical model has been a helpful resource in transforming teaching and learning at her school.

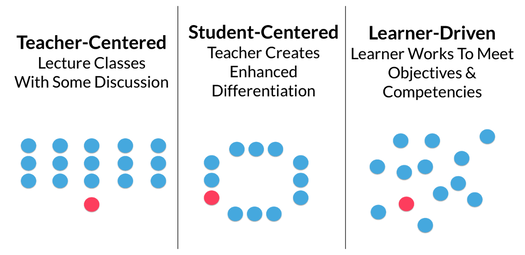

Brad Rathgeber Brad Rathgeber Over the course of this year, I’ve written about ten lessons that we’ve learned in ten years of online education at One Schoolhouse. This tenth lesson is perhaps the most relevant for classroom teachers, because it is directly transferable to the face-to-face classroom and is easy to implement starting on a very small scale (it can be tried in a single class period). We learned that when students have choice in what, how, and when they learn, they are more engaged in their course work. Honestly, we had a hunch about the “when” part even before we started in online learning. We knew that student schedules were crazy… and that it was unrealistic for us adults in the school community to ask our students to go from 45 minutes of calculus to 45 minutes of discussing Shakespeare to doing a chemistry lab for the next 90 minutes. How could our students concentrate the way they needed to and engage fully with that type of expectation? What we didn’t know was the "how" or "what"… nor did we know that there was good research about giving students choice in “how” and “what.” Larry Ferlazzo identifies four qualities as critical to helping students motivate themselves: autonomy, competence, relatedness, and relevance. These are central to engendering student agency because they build a culture of choice in your classroom. By empowering students to manage themselves, we invite them to the table as partners in their learning, rather than as recipients of our teaching. As a result, students feel respected and safe, which promotes a growth mindset of risk-taking and learning. Daniel Goldman describes this internal motivation as, “a passion to work for internal reasons that go beyond money and status - which are external rewards, - such as an inner vision of what is important in life, a joy in doing something, curiosity in learning, a flow that comes with being immersed in an activity. A propensity to pursue goals with energy and persistence. Hallmarks include a strong drive to achieve, optimism even in the face of failure, and organizational commitment.” This research helped us ask questions about how we could enable student choice within our classrooms — and whether we had more opportunity to do so in an online space with extensive resources abounding. Our first foray into this work was in developing content pathway choice for students… that’s the example you see below. When a student first explores content in a class with us, they are given choice in how to begin… Here the options include a number of online resources, video resources, and textbook resources. Many students find that they have to complete multiple pathways in order to fully grasp the content. Moreover, we were asking these questions at a time when the field of personalized learning was just starting to take shape. We embarked on a long term project on transforming our online classroom to be learner-driven and personalized. Teachers used what they learned over the years about differentiation, creating pathways for students to choose how to access new content, assess their understanding, and apply learning to the real world. This gives students agency — and, importantly, it also gives students relevance, another key factor for engagement that we learned from Ferlazzo.

|

Don't miss our weekly blog posts by joining our newsletter mailing list below:AuthorsBrad Rathgeber (he/him/his) Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed