Liz Katz Liz Katz There’s a student sitting in your office, telling you that he’s just gotten the chance he’s been working towards for twelve years: an apprenticeship at a professional dance company on the other side of the country. Another student comes in: she’s been offered a prestigious internship at an epigenetics lab in your city, but she has to be on site starting at noon every day. These are two of the most dynamic and engaged students in your school; they don’t want to withdraw, but they also don’t want to walk away from these amazing opportunities. In the past, most schools haven’t been able to be as flexible as they wanted. When a family called to say they were planning to take a year to live with aging grandparents abroad, the typical responses were to pay full tuition for the year to guarantee the child’s spot, or take the chance of reapplying once you return--if there’s a spot at all. That binary doesn’t feel good to school leaders or families. The COVID-19 pandemic, however, showed schools that there’s a different way to imagine learning and community, one that doesn’t have to be bound by time and space. Online courses, asynchronous work, and telepresence applications now make it possible for schools to support students who want to pursue off-campus experiences without having to sacrifice their academic growth. In 2020 and 2021, schools were forced to experiment with different modalities of learning, from “Zoom school” to self-paced course coursework. As academic leaders gained familiarity with a wide range of online learning platforms, they also learned that although learning online is different than learning in person, it can also be as challenging and engaging as any classroom experience. For more than 100 years, educators have known that getting out of the classroom and into the real world is an opportunity to boost student learning. Online learning is an extension of that progressive approach to schooling. Students who are hungry for authentic engagement outside of the walls of a school can use online courses to create flexible schedules which allow them to pursue their passion. At One Schoolhouse, we’ve worked with schools for years to help students make the most of extraordinary opportunities. An elite archer was able to train at the National Training Center in her junior and senior years, and still graduate with her class. Most years, we work with students who have earned apprenticeships at ballet companies, including the Bolshoi Ballet and San Francisco Ballet. Students like these complete most or all of their academic courses online with One Schoolhouse, and at the same time, stay enrolled at their home schools, which continues to provide services like academic advising and college counseling. In the past sixteen months, we’ve learned how to do school differently. Now, many of our students are looking forward to a Fall 2021 that feels familiar. Some, however, have seen what a new approach to learning can make possible. Schools don’t have to let go of students who want new options and increased flexibility anymore--expanded partnerships and online experiences can keep students close, even when they’re spreading their wings.

0 Comments

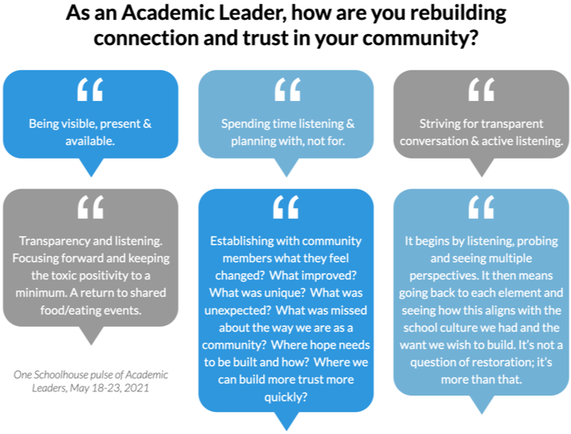

Beta Eaton Beta Eaton Beta Eaton as told to Liz Katz -- When we look ahead to what we can expect of our students in the 2021-2022 school year, we keep thinking about the ways the past fifteen months have been both more challenging and more simple than a typical year for high-achieving students. The challenging pieces are obvious--grappling with a global pandemic, racist systems, and a norm-shattering election year is hard for adults, let alone for children and adolescents. At the same time, our students’ lives were stripped down. When school was online, social structures had less of an impact on adolescents; when sports teams and plays were cancelled, students had fewer competing priorities. For some students, the focus and independence was just what they needed to thrive; others were challenged by isolation and missed opportunities. As a result, students are coming back to school with less practice in the soft skills that are essential for success in high school while at the same time, they’re still emotionally and cognitively processing the upheaval of the past year. Academic leaders and educators need to be aware that their student support systems have to evolve to meet the unique needs of the next few years. At One Schoolhouse, we’ve developed a student support program that meshes with on-campus services. Building a flexible program for students who are new to us every fall has taught us how to expand on schools’ existing programs to be ready for a wide range of situations. Here are some of our key strategies that will help schools prepare for Fall 2021: Emphasize engagement: In 2020-2021, many teachers made the decision to pare down their course content as they adjusted to new modalities of teaching. Some built around competencies, and they were able to preserve their signature projects. Teachers who focused on content, in contrast, frequently gave up projects and hands-on learning--for many students, the most engaging elements of the curriculum. As a result, even when students’ performance stayed strong, enthusiasm and engagement often faltered. Expanding your course catalog with online courses and on-campus offerings, and increasing student-driven and project-based learning opportunities builds the intrinsic motivation that drives students to reach their full potential. Be ready for the unexpected: One of the key lessons we’ve learned doing student support at One Schoolhouse is that when a student is struggling, their situation can pivot quickly from the containable to the critical. This is especially true of students who are already vulnerable. What’s different this year is that your vulnerable group includes every student in your school, no matter how on top of it they seem. Don’t assume that only some students are liable to struggle—the risk is universal and unpredictable. Move small, move fast: Since our students’ risk levels are elevated, we can expect that they may be less able to manage the flexibility and self-advocacy that academic challenge demands. This isn’t the year to wait to see if kids solve their problems on their own. Instead, think about what the smallest possible intervention can be. It can be as simple as checking in with the student on their way out of your classroom, or sending an email reminder about an overdue assignment. Watch how they respond—if a nudge doesn’t activate the student, it’s time to lean into your school’s support networks. Open communication lines between academics and counseling: Academic struggles often indicate that a student is experiencing challenges outside of the classroom. At the same time, known adverse events, whether at home or with peers, often presage academic challenges. In this climate of elevated risk, it’s essential that faculty keep in open communication with the counseling or guidance professionals at your school. Examine your practices to make sure your systems foster the collaboration of caring adults.  Sarah Hanawald Sarah Hanawald As vaccine distribution expands to teens and many restrictions are lifted in the U.S., educators and families are starting to feel hopeful going into the summer and are looking towards the fall with optimism that school will be more “normal.” The promise of an end to the health pandemic is in sight….but it’s not “over” yet. Furthermore, school leaders must continue to engage in equity work to oppose racial injustice. Exhortations to avoid “toxic positivity” have been flooding into my inbox lately in the newsletters I get from various organizations. These articles typically remind the reader to acknowledge that many members of our community are not looking for silver linings but instead are struggling with grief, disillusionment, or other stressors they carry for themselves and others. Some of those losses have been shared. Many have not. This reminder is a timely challenge because often, independent school leaders instinctively reach for appreciative inquiry, asking ourselves “what positives can we identify?” Further, in our school lives, we spend a lot of time helping those around us develop confidence and a growth mindset. Our growth mindsets mean that we encourage students to say “not yet” instead of “I can’t” when they face a setback. This is, in fact, one of our superpowers! Although a growth mindset may be critical for long-term growth, this is not the moment for a “relentlessly cheerful” approach to our work with families, students, or colleagues. The next few months are a time for leaders to demonstrate their empathic awareness by acknowledging the burdens of the past year instead of rushing past them. Authentic resilience emerges not from the moment of crisis, but from the process of moving through the aftermath of the crisis into reconstruction. What’s most essential to that resilience is, unsurprisingly, our connections to one another. Researchers Rob Cross, Karen Dillon, and Danna Greenberg studied the importance of professional networks in building resilience in their members. They write that good leaders build resilience by “shifting perspective and reminding [others that they] are not alone in the fight.” Leaders who say, “This is tough,” or “I can’t fix this for you, but I’ll help you get through it,” have more impact than those who try to minimize difficulties. The researchers identified eight things effective networks provide to their members:

Of course, not all of these factors apply in every situation. Academic leaders who are thoughtful listeners and highly empathetic will consider not just who on their team needs what kind of support, but how best to provide that support and ensure that the timing support is right. One final note, of utmost importance for academic leaders in the coming months is self-awareness too. Leaders should be considering not only the role they play as members of these networks for others, but how to tap into their personal networks for building their own resilience too. Association for Academic Leaders members can sign up for our online course, Supporting Faculty Wellbeing Right Now, April 25 - May 1, 2022, and May 2 - May 8, 2022.

Objectives:

Brad Rathgeber Brad Rathgeber We keep talking about how the dual pandemics have accelerated changes that existed in society pre-pandemics. Can I share with you a revealed change that makes me hopeful going forward? The deep appreciation for and understanding that content covered does not equal content learned. Pre-pandemics, many schools had started down the roads towards competency based learning. Schools seemed to be on a spectrum; from dabbling with to embracing concepts like the Mastery Based Transcript, standards-based grading, Universal Design for Learning, and much more. The pandemics hastened schools’ work in these areas for a simple reason: we had to. As teachers began to plan for this school-year-unlike-any-other, they came to the understanding that a traditional approach of course organization by content was not going to work -- or they came to that understanding at some point during the first semester this year. Moreover, teachers realized that a reckoning with racial injustices required different foci and curricular objectives. Courses, and the allocation of time within them, had to be organized differently -- by competencies, skills, and learning objectives. Now, we’re ready to define the outcomes that we care about driving with our work. This shift in course design hastens another pre-pandemic trend: the shift toward personalization from differentiation. If “competencies gained” is the measure of student learning, rather than “content covered” by the teacher, then there needs to be a deep understanding of where student achievement is on an individual level -- that is, there needs to be deeper appreciation and understanding that students learn differently and at different paces. This shifts faculty work in the classroom from asking the question “How might I present material in a variety of ways in order to reach all my learners?” to “How might I present multiple choices -- pathways, if you will -- in order for students to demonstrate their knowledge and competencies gained?” If we are in agreement that content covered isn’t the same as content learned, then we should also reframe standardized assessment as a diagnostic rather than evaluative tool. Standardized assessments have a place in a post-pandemic world. The annual standardized assessment as record-keeper -- wherein schools use them to document changes in their student population -- has significant implications for everything from enrollment to equity to wellness within our schools. And, if we’re in agreement that enrollment, equity, and wellness are three of the biggest issues facing independent schools post-pandemic, then recasting the curriculum to be designed backwards from rigorous competencies rather than what’s on AP exams is an imperative. And that leads us to the question of how students will demonstrate those competencies. The Advanced Placement testing that’s underway in high schools this week all too often requires a narrow set of skills for success that’s not always tied tightly to the competencies of the course. As a result, the students in those courses tend to be the ones with the skills that align to the exam--and that can leave out too many students who care deeply about the subject matter but don’t fit the learning profile. Instead, if secondary schools rethink their most rigorous and challenging courses to prepare students’ with the competencies and skills to find success in higher education pursuits, then they will be better off. Join us for our courses that are designed to help school leaders and faculty consider how to better align advanced courses with their school’s mission and values, to answer the question “What are we moving towards?”

Gen Z Takes Over: What Academic Leaders Need to Know About Generational Change and Retention5/3/2021  Liz Katz Liz Katz If you think kids and families have changed a lot in the past five years, you’re right—and thanks to COVID-19, those changes are likely to be more apparent as we move forward. The past five years have been different in part because 2016 was the last year that Millennials graduated from high school, and the first year that K-12 education was completely populated by Gen Z. Enrollment management professionals watched this shift start in their applicant pools, and as these students have risen through the school, it’s visible to all educators. Even though Gen Z kids are being raised by two different generations (Generation X and older Millennials), they’ve still been parented in a similar way, and one that’s strikingly different from generations that preceded them. Parents and guardians of Gen Z kids, whether themselves Gen X or Millenials, focus on their child as an individual. They’re cynical about institutions, and they question institutional priorities and practices. They see their child as unique, and they want to make sure the child’s setting optimizes what’s best for them. They cultivate talent, encouraging children to focus early on their strengths--and that’s because these parents and guardians believe that only the best win, and there’s not a lot of room at the top. So when it comes to independent schools, parents and guardians of Gen Z kids have high expectations. They expect individualization, differentiation, and customization, and they have higher expectations of what schools do for families. They also believe that schools should be held accountable if they don’t meet those expectations--and they’re happy to go somewhere else if that happens. In these families, independent school enrollment is a year-to year decision. That’s why retention is more important than ever in enrollment management. Academic leaders looking at those traits of Gen Z parenting know that these folks are more likely to pick up the phone when something’s not meeting their expectations or is headed off the rails. It’s essential to realize that every time an academic leader receives one of those calls, the interaction is also an evaluation of whether the school is able to meet a child’s needs. At the end of my first year at One Schoolhouse, I looked at our list of consortium schools to see which relationships were strongest, and where I needed to cultivate more connections. What I found surprised me: the schools we were most connected to had usually had a low-stakes student issue at some point in the year--for example, an academic dishonesty case on a minor assignment, or a student who had chosen not to complete three weeks of work. As I thought about this, I realized that those challenges were moments when One Schoolhouse demonstrated key traits like integrity and empathy. When we managed conflict well, we proved our value. The same is true for interactions between academic leaders and parents or guardians. Knowing that the parents of our GenZ students are less likely to tolerate bumps in the road provides academic leaders with important opportunities to shore up retention. It’s important to note this doesn’t mean capitulating to a request or acting without integrity. Instead, it’s the time to be an empathic listener, a flexible problem solver, and an ethical educator. If families feel that the problem-solving is transparent, values-focused, and well-communicated, they’re usually going to feel positive about your relationship and comfortable with the resolution, even if it’s not the one they hoped for. (And let’s be honest--if a family wants you to solve a problem with an unethical solution, they’re probably not a family you’re interested in retaining!) The difference between a good school and a great school is invisible when everything’s going well; only the great school shines when times get tough. Those are the moments when families take the measure of a school. When academic leaders solve problems, demonstrate compassion, and communicate effectively, they turn skeptic parents into school promoters. |

Don't miss our weekly blog posts by joining our newsletter mailing list below:AuthorsBrad Rathgeber (he/him/his) Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed