When people encounter a new technology tool, they’re eager, and that feeling drives engagement and adoption. Think about a time you tried a new meditation app, or a fitness tracker--you’re excited to use it! After a few weeks, or maybe even a month, however, it’s not quite as exciting. You stop using it regularly, or maybe even altogether.

That’s the novelty effect--when you adopt a new tech tool, you invest energy and time in it. In the vast majority of situations, however, the novelty effect wears off. In an online learning environment, the timing of this effect is especially important. That’s because the novelty effect wears off just as the course ramps up to its full level of challenge. Students get an energy bump from trying new things, but once they know how the system works and what the expectations are, they settle in and can lose momentum. In those weeks when students are most excited about new challenges, teachers are typically reviewing. This gives students the chance to learn how to learn, before they’re responsible for new material. The time to start learning the new content, however, is generally at exactly the same time that the novelty effect wanes: three to five weeks into the school year. That means that many schools are now in the time frame when students need to rise and meet this challenge. Our resilient students take the opportunity to lean in and push through. Students--especially those who are accustomed to quick success--may get discouraged fast and say, “I can’t learn online.” What they really mean is, “I am uncomfortable and this is harder than I expected.” Most of our students did school just one way until last spring: in person, on a schedule, and with classmates. When a student takes a class in a different format, the familiar markers and cues just aren’t there. Different doesn't mean better or worse; it just means it's a new experience, and new experiences are often uncomfortable. Encourage your students to persist through the discomfort and to see it as a necessary step in learning: “This is challenging right now, but if I keep trying, I will get better at it.” Challenge their assumptions that they can’t succeed in the online space. The fastest way to get better is to video conference with the teacher-- these meetings are more effective than email or messaging, because they allow students to get real-time feedback and solutions, and they reinforce trusted relationships. Finally, make sure your school has identified the advisor, teacher or administrator who’s responsible for checking in regularly with a struggling student. When students know they’re not alone, it’s easier to build confidence and competence.

0 Comments

One of the great joys of opening school at One Schoolhouse is the way that our program opens opportunities to students. Here are just some of the ways we’re making a difference to the 271 schools in our consortium:

As a part of our commitment to diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice, we’ll be recognizing observances and holidays that center the voices and experiences of historically excluded peoples in the United States. As an educational organization, we want to lift up the words of others who share our commitment to learning, and amplify Chicana/o/x, Latina/o/x, and Hispanic voices. Learn about the history of Hispanic Heritage Month: The Library of Congress provides resources and describes the history of Hispanic Heritage Month; NPR’s Code Switch podcast explores the category and identity of “Hispanic” as it is used in the U.S. Recognize Hispanic Heritage Month in your school and community: Access resources and lesson plans for Hispanic Heritage Month at the Anti-Defamation League. We encourage you to seek out the many Latinx voices speaking and writing about Hispanic Heritage Month. One voice: In “La Descolonización de los Idiomas Colonizados”, One Schoolhouse teacher Amanda Rosas describes why she teaches “the brute truths and realities of colonization”: because “we are learning to believe that from conquest blossoms the word resilience, not erasure.”

When I ask faculty, “What does collaboration look like to you?” I receive a variety of answers from giving documents to a colleague to brainstorming. These responses demonstrate to me an appreciation of collaboration skills, but they do not reveal a consistent agreement of what those skills look like. We say we value collaboration, yet what is our shared understanding of the word, and do we consistently practice it? With the goal of collectively creating meaningful learning experiences for our students, last year I concluded we needed a school-wide definition of the word collaboration.

Last October, I enrolled in a One Schoolhouse and Folio Collaborative class, “Creating a Culture of Collaboration.” For one of the assignments, I created an action plan to establish a school-wide definition of collaboration with behavioral norms. In the spirit of collaboration, I brought my idea to our department chairs. The chairs eagerly affirmed such work would continue to help them build effective teams. To inspire thought in an initial activity, I posted one of the class handouts, a list of behavioral norms from Elena Aguilar’s, The Art of Coaching Teams in our Collaboration Space on OneNote. In small groups, I asked chairs to identify five behaviors that spoke to them as a school-wide definition of collaboration. Each group marked their choices in the Collaboration Space so all of us could see the behaviors each group chose. At our next meeting, I used a Folio Collaboration exercise requiring chairs to work individually. Each chair took a few minutes to review Aguilar’s list and defined what good collaboration looked like to them. Each chair shared their list and the reasoning behind their choices with a partner. Together, they identified three behaviors they both shared about effective collaboration and any area of disagreement. Next, each pair created a new list defining what good collaboration looks like. Each pair merged with another pair to form a quad and repeated the process until all the pairs merged into the entire group. We ended up condensing our list to six behaviors. In two additional meetings, we wordsmithed to make each behavior as concise as possible. Our process was efficient, and the result is well-organized and succinct: our six behaviors that define collaboration consist of only 53 words! The professional behaviors that define collaboration will be posted in our Faculty Policies and Procedures and shared with faculty during August in-service. Chairs can now use the shared school-wide definition of collaboration as a foundation to define behaviors and norms for their own departments. Additionally, each grade level team can also use the definition to establish meeting norms. Chairs and I even shared this work during the hiring process with candidates this spring. We asked candidates what effective collaboration looks like to them and how they collaborate with a team. With a shared definition of collaboration, we can now say not only do we value collaboration, but we can consistently demonstrate it. We have a faculty with a variety of superpowers they bring to their teams. No matter what interpersonal dynamics shift, no matter what crisis we encounter, our professional behaviors for Ursuline Collaboration now serve as a roadmap to collaborate in a way that keeps our students in clear focus, maintains effective teams, and helps us move beyond obstacles. Here are the professional behaviors that we identified for our school. Professional Behaviors for Ursuline Collaboration:

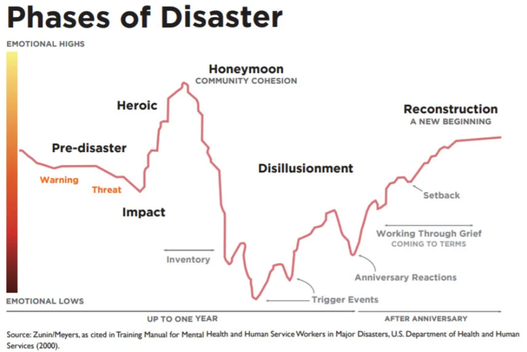

What’s tricky about this disaster model is that it originally modeled a single-impact event like a fire or a hurricane, with a clear delineation between this disaster is happening, right now and this disaster has happened and I am living with the repercussions. That’s not what COVID-19 has been like. Instead, we’ve been living in both those moments at the same time. That duality has been especially hard for educators, because schools have been tasked with functioning as close to typical as is possible, maintaining an illusion of normality. Let’s also not forget that reopening campuses was essential for large-scale economic recovery, because in the United States, elementary education also functions as child care–a truth that privilege often masks in independent schools, but was sharply revealed by school closures. At the start of the 2021-2022 school year, many educators believed we were in the reconstruction phase (or at least moving quickly towards it), and began the academic year as typically as was possible. School practices and policies are built with the assumption that most of the people in them are healthy, both physically and mentally. That simply wasn’t true in Fall 2021. Educators and students were living through abnormal times and still moving through the disillusionment phase. Despite the fact that the setting of education returned to normal (on campus), the people did not. As a result, there was a misalignment between what typically happens in a school setting and what people were capable of doing in that historical moment. Rather than a “works as expected” school year, we experienced tremendous disruption from waves of infections, students’ atypical social and emotional development, and, for some, mental illness. Educators suffered not only from the disruption but also from cognitive dissonance, which is the tension in the mind when it is confronted by conflicting beliefs, or by the difference between one’s beliefs and one’s actions. Both being back on campus, and the larger narrative of recovery in the media told educators that things were back to normal, but their lived experience of upheaval was sharply different. This was exacerbated for Black and Latina/o/x educators and students in independent schools, as communities of color were disproportionately affected by illness, in contrast to the predominantly white institutions where they taught and learned. Human brains don’t like experiencing cognitive dissonance, which creates stress and discomfort, and they really don’t like living with long-term stress. I talked to so many people in the summer of 2022 who felt the 2021-2022 academic year was both less complicated and much harder than the previous one. Why? Because, on top of disruption, we were all living with the effects of cognitive dissonance–believing the year should be typical, and experiencing it as atypical. That’s the “Working through grief,” “Coming to terms,” and “Setbacks” that you see in the diagram above. It’s still part of the disillusionment phase. In the title of this blog, I promised to tell you why this year should be better. For the first time in two and a half years, I’m optimistic about the start of the school year. That’s because we’re getting better at managing disruption, and Academic Leaders are starting to resolve cognitive dissonance. Disruption is receding. The way we live with COVID-19 is becoming predictable, and we’ve become realistic about the ways that living through the pandemic has affected us. Schools have settled into research-backed protocols for exposure and infection, and the wide spread of multiple variants is moving us ever closer to an endemic state. Cognitive dissonance resolves when humans change. They either change their dissonant beliefs so they’re no longer in conflict with each other, or they change their actions so they’re no longer in conflict with their beliefs. Educators have a better understanding of their students’ social, emotional, and cognitive growth, and are meeting their students where they are. Academic Leaders have a clearer sense of the ways teachers have been tried and tested over the past two years. We now understand that schools, students, and teachers have been changed by the pandemic, and we have changed the ways our schools function to better serve the way we live now. Is disruption in our control? Absolutely not. Is cognitive dissonance in our control? Yes. When we resolve our conflicting beliefs and actions, we lessen the stress we carry each day. It gets a little easier as we keep going. In 2022-2023, we’re on the path to reconstruction. I know we’ll get there. Citations: 1 -- Despite our best efforts, I’m unable to track down the original citation for this research. The psychological stages of disaster were documented by Diane Myers and H.S. Zunin, in research I see cited variously in 1990, 1994, and 2000. Most sources document the research “as cited” by Diane DeWolfe in 2000’s “Training Manual for Mental Health and Human Service Workers in Major Disasters.” Image: https://region4bhs.org/Portals/0/Stages%20of%20Disaster%20NE%20Strong%20Flyer%202.pdf?ver=2019-09-11-102019-690 |

Don't miss our weekly blog posts by joining our newsletter mailing list below:AuthorsBrad Rathgeber (he/him/his) Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed