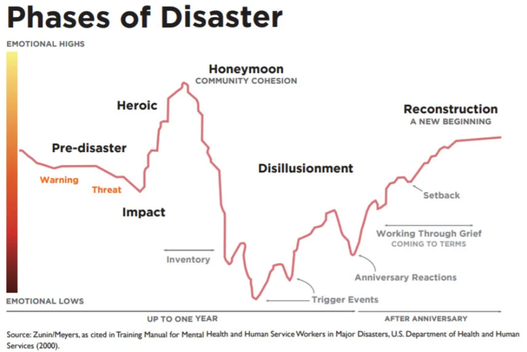

What’s tricky about this disaster model is that it originally modeled a single-impact event like a fire or a hurricane, with a clear delineation between this disaster is happening, right now and this disaster has happened and I am living with the repercussions. That’s not what COVID-19 has been like. Instead, we’ve been living in both those moments at the same time. That duality has been especially hard for educators, because schools have been tasked with functioning as close to typical as is possible, maintaining an illusion of normality. Let’s also not forget that reopening campuses was essential for large-scale economic recovery, because in the United States, elementary education also functions as child care–a truth that privilege often masks in independent schools, but was sharply revealed by school closures. At the start of the 2021-2022 school year, many educators believed we were in the reconstruction phase (or at least moving quickly towards it), and began the academic year as typically as was possible. School practices and policies are built with the assumption that most of the people in them are healthy, both physically and mentally. That simply wasn’t true in Fall 2021. Educators and students were living through abnormal times and still moving through the disillusionment phase. Despite the fact that the setting of education returned to normal (on campus), the people did not. As a result, there was a misalignment between what typically happens in a school setting and what people were capable of doing in that historical moment. Rather than a “works as expected” school year, we experienced tremendous disruption from waves of infections, students’ atypical social and emotional development, and, for some, mental illness. Educators suffered not only from the disruption but also from cognitive dissonance, which is the tension in the mind when it is confronted by conflicting beliefs, or by the difference between one’s beliefs and one’s actions. Both being back on campus, and the larger narrative of recovery in the media told educators that things were back to normal, but their lived experience of upheaval was sharply different. This was exacerbated for Black and Latina/o/x educators and students in independent schools, as communities of color were disproportionately affected by illness, in contrast to the predominantly white institutions where they taught and learned. Human brains don’t like experiencing cognitive dissonance, which creates stress and discomfort, and they really don’t like living with long-term stress. I talked to so many people in the summer of 2022 who felt the 2021-2022 academic year was both less complicated and much harder than the previous one. Why? Because, on top of disruption, we were all living with the effects of cognitive dissonance–believing the year should be typical, and experiencing it as atypical. That’s the “Working through grief,” “Coming to terms,” and “Setbacks” that you see in the diagram above. It’s still part of the disillusionment phase. In the title of this blog, I promised to tell you why this year should be better. For the first time in two and a half years, I’m optimistic about the start of the school year. That’s because we’re getting better at managing disruption, and Academic Leaders are starting to resolve cognitive dissonance. Disruption is receding. The way we live with COVID-19 is becoming predictable, and we’ve become realistic about the ways that living through the pandemic has affected us. Schools have settled into research-backed protocols for exposure and infection, and the wide spread of multiple variants is moving us ever closer to an endemic state. Cognitive dissonance resolves when humans change. They either change their dissonant beliefs so they’re no longer in conflict with each other, or they change their actions so they’re no longer in conflict with their beliefs. Educators have a better understanding of their students’ social, emotional, and cognitive growth, and are meeting their students where they are. Academic Leaders have a clearer sense of the ways teachers have been tried and tested over the past two years. We now understand that schools, students, and teachers have been changed by the pandemic, and we have changed the ways our schools function to better serve the way we live now. Is disruption in our control? Absolutely not. Is cognitive dissonance in our control? Yes. When we resolve our conflicting beliefs and actions, we lessen the stress we carry each day. It gets a little easier as we keep going. In 2022-2023, we’re on the path to reconstruction. I know we’ll get there. Citations: 1 -- Despite our best efforts, I’m unable to track down the original citation for this research. The psychological stages of disaster were documented by Diane Myers and H.S. Zunin, in research I see cited variously in 1990, 1994, and 2000. Most sources document the research “as cited” by Diane DeWolfe in 2000’s “Training Manual for Mental Health and Human Service Workers in Major Disasters.” Image: https://region4bhs.org/Portals/0/Stages%20of%20Disaster%20NE%20Strong%20Flyer%202.pdf?ver=2019-09-11-102019-690

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Don't miss our weekly blog posts by joining our newsletter mailing list below:AuthorsBrad Rathgeber (he/him/his) Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed