Important work needed to be done, and if we didn’t do it we would just start the next year behind. That turned out not to be true. We had a celebration and everyone excitedly moved on into summer. Work got done: comments were written, grades were submitted, but it was done asynchronously. Some people even met, but they had the autonomy to do it when and where they wanted. Instead of meeting, what we did was celebrate – on the same day as graduation – and then rest, both of which were well deserved and much needed. No one missed these end of the year meetings. Shocker, I know! In fact, I’ll confess that only one year after abandoning these meetings, I just had to look up old schedules to remember what we had met about in the “COVID before-times.” Whether over or not, we seem to be moving on from the pandemic, and we are taking seriously the idea that in many ways we shouldn’t just return to “normal.” And one of the ways in which we are doing this at Miss Porter’s is by not going back to having end of the year meetings. While it hasn’t been quite as challenging a year as last, when we get to graduation, people will still be exhausted, and so the least we can give them is some autonomy with regard to how they use their time. Grading will get done, comments will get written, some departments and committees will meet, but they can schedule these meetings whenever they want over the summer, and the same will be true for one-on-one meetings that supervisors have with all faculty members. This takes some stress and pressure off of the end of the year, and that excitement we all feel at graduation can carry into the next week, without the dread of having to be in a meeting at 8am on Monday. On an episode of NAIS’s New View EDU podcast this past winter, Jay McTighe said the following: “I'm an advocate for summer work, whether it's summer curriculum work or designing for project-based learning, or more authentic assessments. Because what I call the heavy lifting of curriculum and assessment design is just too hard to do in the middle of the school year with occasional meetings here or a substitute day there. By the way, the implication should be straightforward, especially in schools that don't have a history of summer work. We need to build that capacity. We need to agree on what we need to work on. We need to invite the right people to come work on it. We need to set the dates well in advance so people can plan their summers accordingly, and we need to budget for it. We need to pay people for work outside of the teaching day.” We were inspired by this, so one thing we have added this year is what we are referring to as our first annual curriculum writing institute. In place of meetings, teachers have been given the opportunity to opt into this curriculum writing institute, and they will get paid for this additional work writing curriculum for programs and courses that reflect institutional priorities. So for some teachers there will be work, but it will be optional, it will be generative, and it will be paid. McTighe is correct – this curriculum work can’t get done during the school year, especially when you are trying to do a complete overhaul of your curriculum as we are at Miss Porter’s in preparation for our transition to a full mastery-based program and the eventual issuing of a Mastery Transcript.

Thus, we’ve reduced some of the stress of the end of the year, people are given autonomy, and choice, some are able to earn additional income, and real important work that moves the school forward gets done. So go ahead, follow our lead and cancel those end of the year meetings. I promise your faculty won’t mind!

0 Comments

When we were preparing to launch the Association for Academic Leaders, we did our homework. In surveys and interviews, we asked Academic Leaders what they needed in order to do their jobs well. We heard clearly that it’s too easy to get swept into the day-to-day work. Academic Leaders want to have easy access to big ideas and the research that supports change.

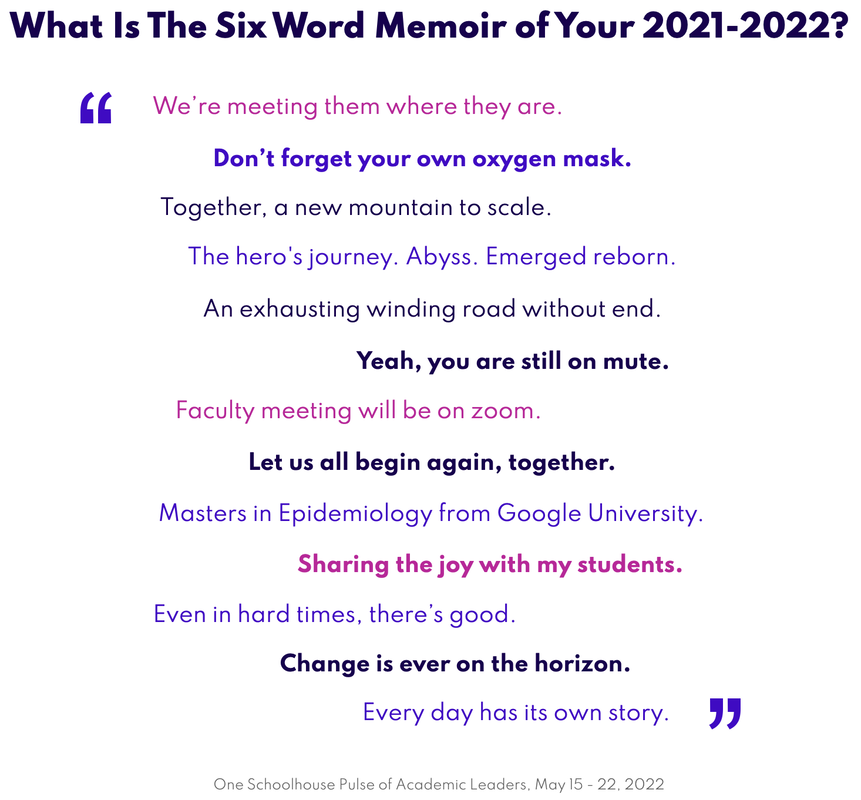

This week, we’re launching a new member-exclusive resource we expect to build annually. Magazines and newspapers do their year in review pieces in December, collating the reporting, review, and, think pieces that have made an impact. Looking back in December, however, doesn’t make sense for educators. As part of schools’ member benefits, they’ll receive Marking the Moment 2022, a slide deck and resource list that brings together research and analysis to tell the story of the academic year we’re finishing this May. This project is designed to provide a conceptual framework that allows Academic Leaders to see trends and data in the context of the narrative of the school year, and to present the sources that allow you to dig deeper. Marking the Moment 2022 includes explorations of topics including technology, teacher retention, standardized testing, and the mental health crisis. Each of these connects Academic Leaders to key data points and research that they can use to explore the issue with teammates, teachers, and families, and takeaways that can help focus questions and find answers. If you’d like to learn more about Marking the Moment and the Association for Academic Leaders, please reach out to Sarah Hanawald, Senior Director of the Association. It’s been a year–and these stories matter. Six-word-memoirs ask the writer to distill an experience into a string of six words that capture an experience. Take a look at high school students’ six-word memoirs from this past fall, or these six-word memoirs.

More than twenty-five years ago, before social-emotional learning was part of the broader lexicon, the faculty at Georgetown Visitation Preparatory School in Washington DC took a close look at their student wellness. They noticed that eleventh grade saw a convergence of heavy reading loads in both English and U.S. History classes, and students were choosing to give up electives such as Studio Art in order to have more free time during the day.

In addition, intensive study gave students a new perspective. By focusing intently on a single topic, students saw the themes and patterns of American history with a new clarity. The course was easier and more engrossing in the summer, one student said, because “ideas touch.” Sue Foreman, Academic Dean at Georgetown Visitation, describes the summer course as helping students to “connect the dots” because of their immersion in the content. Then came the pandemic. Offering a summer course on campus was impossible, but the school knew that the option of summer work was still a vital need for their students. As a long-standing member of the One Schoolhouse consortium, Visitation turned to One Schoolhouse and their Summer 2020 US History course.

One Schoolhouse’s for-credit summer courses help students to complete requirements in the summer and pursue their academic goals on campus in the fall. Explore this summer's offerings here.

Let’s start with why. When you share questions in advance, you bring your organization’s priorities to the forefront, allowing a candidate to determine whether they find those a good match for their goals. The candidate can explain the alignment to you during that first conversation. And if the candidate doesn’t have an appropriate answer to a question that was shared in advance, that’s illuminating too.

Another compelling reason for sharing questions in advance is that you stop privileging extroverted fast processors during the interview times. During our webinar last week, Amber Stockham, SPHR, NBOA’s Director of Human Resources Programs, pointed out that schools lose when the interview process is not in synch with the actual expectations of the role. Finally, offering the questions in advance helps individuals who may not be as experienced in interviewing prepare–whether it’s because they are early career or have been in their current role for many years. Just because someone needs time to prepare doesn’t mean they aren’t a great candidate. Of course, every answer is going to lead to opportunities to elaborate, for the interviewer and the candidate. Don’t worry that providing the interview questions in advance will lead you to a scripted experience. Instead, see it as an opportunity to bring out your curiosity and flex your empathy muscles and you take the interview to the next level with probing follow-up questions that will be more individualized. |

Don't miss our weekly blog posts by joining our newsletter mailing list below:AuthorsBrad Rathgeber (he/him/his) Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed