Sarah Hanawald Sarah Hanawald As we head deeper into September, we find ourselves in the midst of back-to-school nights, meet-the-teacher events, and more. Over the past year and a half, distance learning provided many parents and guardians with the opportunity to see into their child’s classroom (a sharp difference from the access they had pre-pandemic, when some schools shared little more than term grades and critical updates). Now that students are back on campus, some families want to continue having access to their students’ academic experience. It’s tempting to say, “We don’t do that,” but simply closing the window to their view may be counter-productive. In fact, it’s important to realize that some of the adaptations that schools developed are likely to become standard practice. “We’re doing almost all our parent and guardian meetings remotely now—--and we couldn’t be happier!” We’ve heard this comment over and over in conversations with academic leaders about how they’ve adapted pandemic strategies for the future. Online meetings allow academic leaders to make crucial connections while minimizing disruptions to work or family schedules. As a former tech director, it warms my heart to learn that technology facilitates personal connection and interactions. Maybe that power to connect via video conference is really just the tip of the iceberg. During the last year, campus leaders engaged in massive system overhauls, both structural and virtual, to better support students and their families. This year is the time to figure out how these new systems might enable us to provide families with insights, rather than just information. Just as my colleague, Liz Katz, charged school leaders with using our LMS to power-up new faculty onboarding, let’s consider what else can we power-up with our new capabilities. Providing parents and guardians with total access to classrooms and courses would be inappropriate both in terms of community norms and students’ developmentally appropriate autonomy. However, there are ways in which giving parents insight into their students’ lives and educational experiences can facilitate connection between the parent/guardian and their students. Every year, parents and other caregivers have lots of questions, and as Academic Leaders, a big part of our job is ensuring those questions are answered, and guiding families in making the best academic decisions for and with their children. Most of us publish course books and progressions, but those overviews don’t capture the classroom experiences that make our schools great. The question now is how to leverage the systems we put in place last year to help build community and connection this year. Let’s recognize that teachers are a key part of this process. Academic Leaders need to help educators understand that effective communication builds trust between families and teachers, which in turn will translate into stronger relationships in the school-home partnership. When families trust teachers, that trust extends to the school as well. Digital systems allow educators to share more than the syllabus and textbooks; instead, they can use their tools to let families know what it’s like to share insights in a fourth grade literature circle, complete a lab in AP Physics, or present about a significant historical event in an eighth grade assembly. The great gift of digital resources is how easily they can be shared, minimizing the burden on teachers and maximizing benefits to families. A video of an experiment that a teacher created last year can be embedded in this year’s back-to-school night PDF, or in next year’s course selection materials, making the experience more dynamic and engaging. Lower-tech works too. Laura Cox, a humanities teacher at Marin Country Day, takes the poem she reads to her classes every day, and sends it out to an opt-in parent/guardian email list. These messages give parents a sense of classroom discussions, articulate Laura’s goals for her students, and provide an opportunity for families to extend the conversation at home. As we move closer to post-pandemic life, the technology that schools used as a solution for social distancing can now be repurposed to bring more connection to our campuses. Digital systems and resources are an essential new tool for strengthening the home-school partnership and inviting parents and guardians into the lived experience of the classroom--an essential element for building the relationships that make independent schools so strong. What else can you think of that might pose a creative use of your newfound technical expertise to invite parents and guardians into the lived experiences of their children?

1 Comment

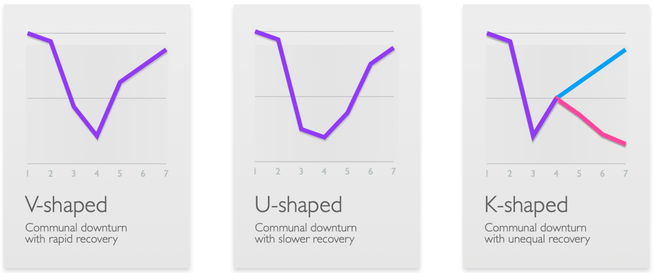

Liz Katz Liz Katz Early on in the pandemic, I asked a friend what she was hearing from parents, guardians, and caretakers at her school. She answered, “They’re all worried their kids are going to be behind.” Even after that night, I kept thinking about the word behind, and all the parental anxieties and preoccupations it revealed: that growth should be linear, that students are being measured against each other, that “success” as they define it is a scarce good, with limited access. Months later, I was reminded of that conversation as I read articles describing recovery from the global and domestic recession as K-shaped. Most economic downturns, when plotted on a matrix, are V-shaped or U-shaped: they drop sharply, then turn back upwards, for all sectors. A K-shape reveals that the recession has widened income inequality. After a short universal upturn, the wealthy continue on the path to economic recovery, but poor and working-class families’ growth reverses—they revert to a downturn. Parents and guardians are managing two acute sets of anxieties. The first revolves around their child’s emergence from the social and emotional impacts of the past eighteen months—how they are now as life returns to its usual trappings. The second set of anxieties concerns what comes next. With all indicators pointing to expanding inequality, parents and guardians feel urgency to ensure that their children will have access to opportunity as they launch into adulthood. In essence, they are searching for certainty in an increasingly uncertain world. The truth is that the phrase “kids are resilient, they’ll be fine” that parents have been hearing over and over doesn’t align with their plans; “just fine” isn’t what they aspire to for their child.

Within this context, parents and guardians are trying to create certainty wherever they can by making sure their child has access to every possible opportunity. This may include anything from an opportunity to perform on stage, compete in an academic competition, or play on a sports team. Then there are those who are anxious about a transition to the next educational institution, and that admission is a limited resource with a zero-sum outcome; and parents didn’t know how to prep their kids to excel in pandemic learning. If parents and guardians perceive that an academic leader or an institution is putting up a barrier to an opportunity, they will react from a place of fear or anger—emotions that make it difficult to maintain a sense of perspective and proportion. As academic leaders, when managing family anxieties, one of the most important things to do is reject the intimidating influence of generalization. In order to work well with these parents and guardians, really listen to and acknowledge their concerns. Don’t serve up platitudes. Instead, put their concerns in context. Address the relevant social factors, but also reassure them by demonstrating how well you know their specific child—their strengths, their interests, their particular struggles. Make sure they know that you know that their child is not just a statistic or a trend. Educators are not going to get rid of parent and guardian anxiety, because anxiety is a natural cognitive process, even at the best of times. (These are not the best of times.) Minimizing or ignoring those anxieties doesn’t resolve the issue; instead, it alienates parents from the educators who have the power to diffuse their fears. By addressing parents’ and guardians’ worries with empathy, perspective, and clarity, we can help them move through their fears and support their children.

Add on top of that the trauma everyone still and continues to have. Last week, the New York Times journalist Kara Swisher interviewed Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers, on her podcast Sway. In that interview, Weingarten said: “COVID affected all of us differently. Communities that were poor, black, and brown got more affected. [COVID] created lots of trauma. And then having leadership that was more political as opposed to more focused on the health and safety of America was really problematic. So we have you know that crisis and then on top of it we had the death of George Floyd and then on top of it a 2020 election and then an Insurrection. So there's huge trauma… When people are so traumatized, when there's a question about future, when there's a question about what's going to happen to my kids, what’s going to happen in a year from now, my kids didn't get the graduation, they didn’t have kindergarten. It becomes easy to exploit this, and that's what I think is happening.” We have trauma being exploited on a number of levels, both hyper locally and nationally.

As Academic Leaders in independent schools, we have fewer tools for community and trust building that we had before and the tools that we do have are different (requiring us to build new skills), all at a time when we are surrounded by and experiencing trauma ourselves--meaning that building trust is more essential than ever. We had hoped that we could go back to our old tools of in-person connection this fall, but with the resurgence of COVID-19 outbreaks, being together in person is only an option for some of our families in some of our schools, and some of our communities. Returning to our old strategies and leaving out the people who aren’t ready or able to join us on campus isn’t an option, because it magnifies and expands the inequities that are already present on our campuses. We know that the COVID-19 pandemic is greatly impacting the health and well-being of our students, worrying parents and guardians further. A recent McKinsey survey noted that: “Roughly 80 percent of parents had some level of concern about their child’s mental health or social and emotional health and development since the pandemic began… Parents also report increases in clinical mental health conditions among their children, with a five-percentage-point increase in anxiety and a six-percentage-point increase in depression.” The CDC notes a 7 percent increase in mental health events among 5-11 and 12-17 year olds respectively during the COVID pandemic. And in turn, parents and caretakers themselves have reported elevated levels of stress. An APA study notes that 46% of parents have a high level of stress compared to 28% of non-parents. Parents and guardians need their schools to be partners in order to have a positive impact on the life of kids as never before. That’s why we’ll be exploring how Academic Leaders can work effectively with families and expand trust and connection within their communities throughout this month. |

Don't miss our weekly blog posts by joining our newsletter mailing list below:AuthorsBrad Rathgeber (he/him/his) Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed