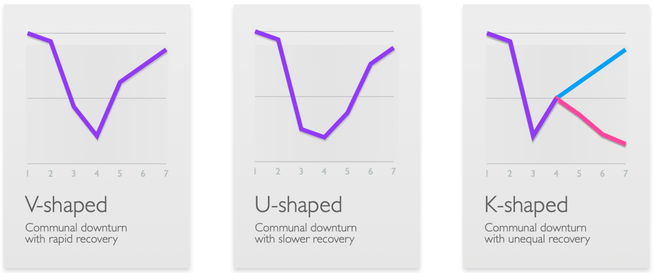

Liz Katz Liz Katz Early on in the pandemic, I asked a friend what she was hearing from parents, guardians, and caretakers at her school. She answered, “They’re all worried their kids are going to be behind.” Even after that night, I kept thinking about the word behind, and all the parental anxieties and preoccupations it revealed: that growth should be linear, that students are being measured against each other, that “success” as they define it is a scarce good, with limited access. Months later, I was reminded of that conversation as I read articles describing recovery from the global and domestic recession as K-shaped. Most economic downturns, when plotted on a matrix, are V-shaped or U-shaped: they drop sharply, then turn back upwards, for all sectors. A K-shape reveals that the recession has widened income inequality. After a short universal upturn, the wealthy continue on the path to economic recovery, but poor and working-class families’ growth reverses—they revert to a downturn. Parents and guardians are managing two acute sets of anxieties. The first revolves around their child’s emergence from the social and emotional impacts of the past eighteen months—how they are now as life returns to its usual trappings. The second set of anxieties concerns what comes next. With all indicators pointing to expanding inequality, parents and guardians feel urgency to ensure that their children will have access to opportunity as they launch into adulthood. In essence, they are searching for certainty in an increasingly uncertain world. The truth is that the phrase “kids are resilient, they’ll be fine” that parents have been hearing over and over doesn’t align with their plans; “just fine” isn’t what they aspire to for their child.

Within this context, parents and guardians are trying to create certainty wherever they can by making sure their child has access to every possible opportunity. This may include anything from an opportunity to perform on stage, compete in an academic competition, or play on a sports team. Then there are those who are anxious about a transition to the next educational institution, and that admission is a limited resource with a zero-sum outcome; and parents didn’t know how to prep their kids to excel in pandemic learning. If parents and guardians perceive that an academic leader or an institution is putting up a barrier to an opportunity, they will react from a place of fear or anger—emotions that make it difficult to maintain a sense of perspective and proportion. As academic leaders, when managing family anxieties, one of the most important things to do is reject the intimidating influence of generalization. In order to work well with these parents and guardians, really listen to and acknowledge their concerns. Don’t serve up platitudes. Instead, put their concerns in context. Address the relevant social factors, but also reassure them by demonstrating how well you know their specific child—their strengths, their interests, their particular struggles. Make sure they know that you know that their child is not just a statistic or a trend. Educators are not going to get rid of parent and guardian anxiety, because anxiety is a natural cognitive process, even at the best of times. (These are not the best of times.) Minimizing or ignoring those anxieties doesn’t resolve the issue; instead, it alienates parents from the educators who have the power to diffuse their fears. By addressing parents’ and guardians’ worries with empathy, perspective, and clarity, we can help them move through their fears and support their children.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Don't miss our weekly blog posts by joining our newsletter mailing list below:AuthorsBrad Rathgeber (he/him/his) Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed