Like a lot of new initiatives, launching points for DEI programs vary widely in schools. The diversity in the website pictures, rainbow ribbons on the bulletin boards, BLM posters in the hallway, and Lunar New Year festivities say, “You are welcome here.” But what’s beyond the welcome mat? In most of our schools, there is a multi-year, all-constituent facing initiative around equity and inclusion. And, in most of our schools, the BIPOC and LGBTQ+ students experience a diminished sense of belonging than that of the straight white students. We’re getting better at leveraging our curriculum to expand empathy and build global citizenship in our students, but if we are paying attention to critical narratives of BIPOC and LGBTQ+ members of our communities, the white heteronormative families are the ones “experiencing” our diversity initiatives. (Cue national outrage around critical race theory over the last year.) So let’s shift gears. In addition to your DEI initiative, do you have an SEL initiative? What does SEL look like for your BIPOC/LGBTQ+ students? When we at One Schoolhouse asked this question, we quickly slipped into deficit thinking as we acknowledged what’s missing. But the other side of that coin is community--and community can’t wait until the phase of the strategic plan where the DEI and SEL initiatives intersect. While we all work to create more wholesome, inclusive communities, we decided that, here at One Schoolhouse, our DEI starting place would be students, and would specifically be identity-honoring spaces for BIPOC/LGBTQ+ students. We have built a series of courses that center identity, places where students can dynamically and critically explore issues of identity, power, liberation, and allyship with peers and a teacher with both personal experience and professional expertise. Our identity courses give students the academic framework to understand their personal experiences from a different perspective. In historically and predominantly white institutions, the experiences of BIPOC/LGBTQ+ students are regularly seen as unique outliers, as stories that challenge but ultimately don’t change the dominant narrative of the school. When these students take courses that correct the erasures and untruths of systemic bias, BIPOC and LGBTQ+ experiences occupy the center rather than the margin. And every year, students tell us that they had no idea there were students just like them in schools across the country. This is how we measure belonging. Equity and emotional safety go hand in hand. If you’re trying to do them separately, you’re missing the point. So be brave. Let your students know about our Asian, Black, Latinx/o/a, and Gender Identity courses. Have a student who feels ostracized in your community but isn’t drawn to one of our identity courses? We center identity in all of our courses. Every course, even the most traditional of the AP courses, makes space for students of all identities to see themselves in the curriculum. Schools are institutions, and it takes time to shift systems to become truly equitable and just institutions. Our current students, however, can't wait for institutional change--they need equity and emotional safety now. Courses that give students an authentic sense of belonging are an opportunity to deliver on your promise to all your families.

0 Comments

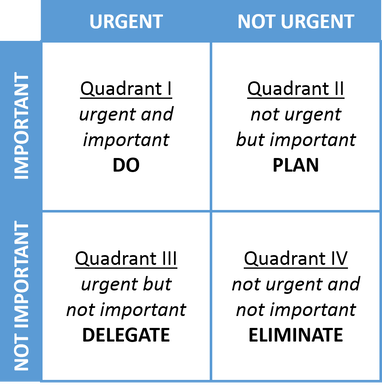

Liz Katz Liz Katz Academic Leaders, I’m worried about you. I’ve been in awe watching you over the past year and a half. You balanced the needs of your students, faculty, staff, and families as you responded to a crisis that few of us had the training or expertise to handle, and you did it with grace, wit, and patience. You’ve been faced with decision after decision in response to circumstances and policies that were far outside your control, and far too often, it felt like even the best possible solution fell short of the ideal. And let’s be honest--it took a lot out of you. That’s because making decisions is like lifting weights--you build your strength by practicing regularly over time, but if you try to do too much at once, you run out of power. Last week, we asked Academic Leaders what kind of issues they were working on as school gets started. 96% of our respondents said they were working on problems that are both urgent and important: high stakes decisions that consume time and energy. If we go back to our weight-lifting comparison, it’s like you’re lifting more weight and doing more reps, and that means you’re tiring out faster than ever. If we take away the simile, you’re stuck in what social psychologists call decision fatigue. Human brains expend a lot of energy making decisions, and as they run out of energy, it becomes harder to make decisions well. In other words, there are physiological and cognitive explanations for why it’s easy to get overwhelmed by the number of problems you have to solve. Researchers who study this phenomenon have documented concrete approaches to managing and minimizing decision fatigue. Here are three of your most effective strategies:

When I say I’m worried about you, Academic Leaders, it’s only because I see how much you’ve shouldered in the past year and a half. I want to make sure you’re doing okay, and I want you to have every tool available to make your work as manageable and visionary as possible. If you can separate out the skill of decision-making from the decisions themselves, they become easier to approach--and this is the year when you deserve to have things a little easier.

A quick search will reveal countless versions, some designed with educators in mind. (You can even buy a planner set up to mimic the matrix!) The basics are a four-quadrant matrix with two axis, Important/Not Important, and Urgent/Not Urgent: In this matrix, the urgent and important (Quadrant I) must be addressed first, within a deadline that is likely to be externally imposed. These are items to resolve decisively and as swiftly as is feasible.

The second step is to understand that Quadrant III items, the urgent but not important, are still important to someone in the organization (or perhaps a regulatory entity) even if they are not important to the overall organization or to you. (If they aren’t important to anyone, they would be in Quadrant IV). Therefore, Academic Leaders should delegate Quadrant III items to the right person, with a timeline, direction, and agency. When these urgent matters are satisfactorily addressed or assigned, the academic leader can return to Quadrant II, which is the mission-driven academic program work essential to a strong and functioning school. The key to using the Eisenhower matrix effectively is never to lose sight of Quadrant II: Not Urgent But Important. If neglected too long, these items become a crisis or a quagmire, they can cause entire programs to fail. Commit to returning to this quadrant and ensure that colleagues are on the same page about what belongs here. Oh...and Quadrant IV? There’s a round basket for filing those right next to your desk. Image Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:7_habits_decision-making_matrix.png  Peter Gow Peter Gow Well, I guess it’s too late in some parts of North America, but in many others the time of teacher and student “orientation” is nearly upon us—when schools everywhere set aside a day or more to gather groups together to prepare for a year of collaboration and productivity. At just about the time I got into this business, the good thinking of social psychologists began to penetrate the world of independent schools, and so “team building” and “group process” exercises became a regular part of these orientational get-togethers. Students and teachers alike experienced softball games, ropes courses, and the dreaded trust fall, all in the name of group solidarity and a little pre-school-year entertainment. Time and a deluge of corporate-inspired newer, cooler exercises have upgraded activity menus, at least in terms of novelty and perhaps even efficacy. Maybe a few days in the woods has gotten old, but how about a trapeze or slack wire? How about having an improv group come to coach the tenth-grade advising team? So here we are, and I know that many readers would look forward to diving into any and all of these and being there to help students process “Yes, and” or “One Word at a Time.” For many people, such activities are probably happy reminders of fun times at camp, in college, or around the family game table. Stepping now into my role as a curmudgeon, I am going to offer another perspective and a caution. I won’t dwell on my own upbringing in a family where games were not played and tents or horseshoes never pitched, nor on having been the fat, uncoordinated kid at camp and everywhere else, though some of you may relate. You have colleagues and students for whom stepping into the game circle is like climbing out of the trenches into machine-gun fire. In some households there may not have been the resources, the family time, or the cultural practice of fun and games. Some people find certain kinds of games culturally or spiritually anathema. Asking these folks to do things that are unfamiliar for reasons of upbringing, culture, or limited resources can cause pain and even shame. Then there are those whose self-consciousness for reasons that you would and could never guess makes participation in certain kinds of activities a source of extreme discomfort. Or people dealing with trauma that you (and possibly they) neither know or understand. Some are just physically or socially insecure. The educator in you wants to respond, “But, hey, that’s the point! To help people develop the confidence to jump in and participate, to take personal risks as part of a growth process and to gain trust in the group.” True. Many people, most people, seem to enjoy these group activities. But some do not, and they either participate, perhaps ineptly, or choose to step away—feeling watched and judged—at a significant cost to their self-esteem. Many years ago I was part of an eighth-grade trip to a wilderness education center. One afternoon the onsite ropes course instructor decided a shy, overweight kid should climb a knotted rope. The instructor started with all his positive reinforcement tools and language, but the kid wasn’t buying it. The instructor ramped up the cajoling, ranging between upbeat and positive and stern and dismissive of the student’s “defeatist” attitude. I had once been that kid myself, sure, but what I also knew in this case was that this child’s life was ruled by an anxious, overbearing parent. I watched the kid stand there, shamefaced, looking at the ground and surreptitiously wiping away tears. Then the kid looked straight at the instructor and said, “No! I’m not gonna do it!” The language may have strayed into the more colorful, but the message was what mattered. I took the instructor by the arm and pulled him aside. I had realized something: this might have been the first time this child had ever spoken had ever put their foot down and said NO! to an adult. I gave the short version of my thought to the instructor, who got it. Later he told me he’d never thought of refusal as an act of courage. Well, don’t we spend a lot of time and energy exhorting kids to say no to peer pressure, to bad decisions—that sometimes refusing is BRAVE? If we’re promoting and facilitating fun-for-most group activities, we must find ways of letting people who really don’t want to participate opt out without their demurral having to be an act of courage. Educators know that shame and embarrassment kill learning. We need to provide pathways for the truly uncomfortable to choose nonparticipation without making them feel stigmatized or humiliated. At One Schoolhouse we’re fans of providing pathways to learning based on students’ interests and proclivities; we even do this in our professional development courses. How about offering choices when we’re charging into the woods or doing improv or whatever else we’ve planned to help our communities develop cohesion? Why not? TO BE CLEAR: If an activity or exercise, particularly for faculty, bears on the strategic work and mission of the school or on preparing folks to work more effectively with students, opt-out should not be an option—but even then, are there multiple paths to the same goals that would play to all participants’ desires to learn and improve? An end note: As an adult I spent many, many summers working happily in camps, and the many board-game boxes in my house are about worn out. I hiked high peaks before the knees went, but I never could and never will climb a rope. And, yes, I opt out of things when I’m comfortable; I learned to live with my shame sixty years ago. But other people shouldn’t have to.

Because of the emotions that are wrapped up in student schedules, it’s especially important for schools to solve these problems quickly and effectively. Our partnerships provide the flexibility and range of courses individual students need without compromising a school’s purpose-built schedule. The key to that flexibility is asynchronous learning.

In the early days of crisis distance learning, asynchronous coursework unfairly earned a bad reputation for being unengaging and impersonal. The key to understanding that reputation is the context of “crisis”: anything that’s built quickly and under stress isn’t going to meet the standard of intentional and expert design--which is exactly what students and families expect from independent schools. That’s why expert and intentional design is the hallmark of One Schoolhouse’s student courses. We begin by building a faculty comprised of experienced independent school teachers who are experts in their fields. (92% of them hold advanced degrees!) We’ve learned that great classroom teachers need additional competencies and skills to become extraordinary online instructors, so we train our teachers in building online connections with students, effective online communication, and technological acumen. Asynchronous work allows students to have a personalized experience that aligns to their learning preferences. One student can watch a video to learn a new concept, while another reads a selection from a textbook. And asynchronous assignments don’t have to be self-paced or solitary. Shared weekly due dates ensure that although students complete assignments at the time that works for them, they’re mastering the same content that their classmates are learning. As a result, students have regular opportunities for collaboration and conversation, like writing skits to practice vocabulary and grammar in language courses, or collecting data for a social psychology experiment. When schools use online asynchronous courses strategically, they’re not limited by classroom space, staffing, or singleton sections. It becomes possible for a student to take two courses that meet at the same time, and financially sustainable for a school to offer an advanced math course for just three students. When academic leaders can start the year by finding positive solutions to scheduling problems, they’re starting off with a win. One Schoolhouse can help solve your scheduling or staffing problems this year. Call us at 202.618.3637 or email [email protected] |

Don't miss our weekly blog posts by joining our newsletter mailing list below:AuthorsBrad Rathgeber (he/him/his) Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed