|

When One Schoolhouse began to talk about forming the Association for Academic Leaders, we knew that the organization needed to be built around the authentic voices and lived experiences of people in academic leadership roles. From the start, we talked about how to ensure that the diversity of identities, roles, and perspectives in the academic leadership community would be represented in our work. Our Advisory Council is one way we are making sure voices like yours are heard–and we’re listening carefully to make sure we’re meeting your needs.

We believe that authentic growth and joy in our work emerge from community. During the meeting, our team found ourselves smiling from ear to ear as we watched the group gather on one Zoom screen, faces side by side. Some were long-time professional colleagues; others were known to one another only via listserv interactions. Coming together was both reassuring and invigorating, and we’re excited to do more of it in our webinars, conversations, meetups, and our in-person forum in June. When the Advisory Council met for the first time, they talked about how they’ve engaged with the Academic Leader Competencies in their work, particularly over the last few years. When the conversation turned to the competency “Assess the present, understand the past, and design for the future,” one council member commented, “This is really intimidating.” Others agreed that one person alone couldn’t be expected to have a complete knowledge of their school’s past, keep a very close eye on the immediate demands of the present, and also envision what the future of education might look like. It’s hard right now to think about juggling, let alone growing, all the competencies required for academic leadership. But the great thing is that the process of strengthening these competencies is by necessity collaborative. The competencies cannot be achieved in isolation. To balance past, present and future, Academic Leaders must rely on and learn from each other. Our goal is to bring groups of insightful educators together to spark growth, both for ourselves and our community. The Advisory Council is just one way the Association brings together Academic Leaders so they–so you–are not alone. Take a look at our website, and you’ll see the faces and reflections of our Advisory Council. We think that as you scroll down the page, you’ll find some words that resonate. Maybe you, too, love the moment when students arrive at school, the possibility and promise the morning offers. Maybe you have a mentor whose words of wisdom still echo when you walk into a classroom. When you’re ready to share what you love about being an Academic Leader, we’ll be listening to you, too.

0 Comments

One Schoolhouse designs competency-based courses with the student-teacher relationship as the cornerstone of our personalized pedagogy. Courses are intentionally developed to be learner-driven; they are informed by seminal and emerging constructivist education research and by data gathered within our own living practice. The pedagogical approach is designed backwards from competencies and the lessons are personalized to honor learners’ unique needs and identities,1 and to pursue dynamic bilingualism.2 This brief seeks to provide context for how our high school language program is evolving and describe the values that inform our pedagogy. While students have long excelled in our language AP courses, for many years we did not offer full sequence language courses because there was little research to support the efficacy of online language learning at the early levels. The research shows that fewer than 1% of Americans are proficient in the language they studied in traditional classrooms.3 Not wanting this outcome for One Schoolhouse students, our goal is to inspire deep learning so we strive to ensure that the online learning experience increases the effectiveness of second language acquisition. By 2018, we had honed our approaches to delivering the four traditional language competencies – reading, writing, listening, and speaking – in the online space, and therefore endeavored to build out our Chinese and Latin sequences. To these we have subsequently added American Sign Language, French, and Spanish, and have re-leveled our courses with titles Beginning I/II, Intermediate I/II, Advanced I/II, and AP to minimize placement misalignment when students enter mid-program. The limitations of other online language programs -- namely, the focus on the “Five C’s” -- are mitigated by the centrality of the student-teacher relationship, including interactive sessions where students speak, listen, and translate with their peers and teacher, at One Schoolhouse.4 J.C. Narcy-Combes’s research on second language learning online shows that “meaningful interaction will trigger learning processes,” which we know to be true anecdotally, and that, with intentional design, students can be taught to learn language effectively online.5 Carrier et. al. have also shown that educational technologies and online learning are rapidly transforming second language acquisition, and that intentional practice can create a highly effective digital experience.6 Because One Schoolhouse students have pathway options where they can practice in the target language at their own pace, get feedback from their teacher, interact with peers from around the country or world, and demonstrate their progress through both traditional assessments and creative projects, students have the full complement of research-based learning activities in their online courses that you would expect to find in any independent school language program. We go beyond these practices, however, to ensure that our students’ practical skills and world views shift as a result of having studied language at One Schoolhouse. Our school-wide competencies -- to engage in a diverse and changing world and to gain academic maturity -- are cultivated in uniquely intentional ways in our language sequences. Because language and identity are inextricably connected,7 One Schoolhouse does not treat reading, writing, speaking, and listening as the sole markers of proficiency.8 Instead, we employ culturally responsive practices that empower learners to see second language acquisition as part of global citizenship9 and to leverage their online language course to develop self-management, empathic, and interpersonal skills. We endeavor to develop a lifelong passion for diverse linguistic exploration in our students instead of traditional reductive and mastery-inspired acquisition models. Schools have options for where their students begin their language learning sequence and what their culminating experience is. Our Beginning I courses scaffold online language learning gradually. The design explicitly positions students’ perspectives about the history and influences that the target language has had throughout the world and explores issues facing countries, communities, and peoples speaking the language today. Students learn about regional and dialect differences among native speakers as they practice strategies for navigating new and unfamiliar situations in the target language. Students may enter or continue at the Beginning II level and proceed through AP, wherein the growth of students’ global competence, as well as communication language competence, are emphasized and measured. More global or applied culminating experiences are offered at our highest Advanced level course in each language; these courses go beyond the AP curriculum to dive deeply into practical applications or literature. Like applied linguist Donaldo Macedo, in our Advanced courses, we seek to “confront the hold of colonialism and imperialism that inform and shape the relationship between foreign language education and literary studies by asserting that applied linguistics is just as important a tool… as literature or linguistic theory.”10 One Schoolhouse students are well prepared to study abroad or in college, communicate in the language within their communities or while traveling, and participate as emerging bilingual members of society. One Schoolhouse language sequences are taught by different teachers at each level so students have the opportunity to learn from and with teachers of diverse backgrounds. Our teachers are trained in both their language and the best pedagogical practices for delivering language online, have studied in both American and international universities, teach in independent schools around the US, and are AP readers. 1. Dedini, C. & Rathgeber, B. (2021) The Pedagogy of One Schoolhouse. https://www.oneschoolhouse.org/learning-innovation-blog/the-pedagogy-of-one-schoolhouse-january-2021

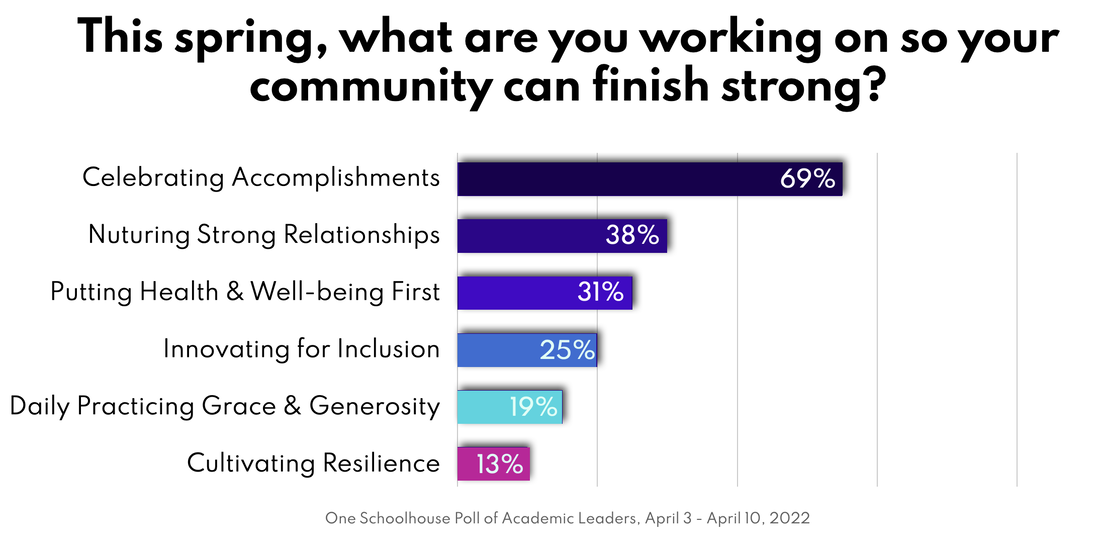

2. García, Ofelia. (2011) Education, multilingualism and translanguaging in the 21st century, Oxford: Oxford University Press 3. Brecht, R. (2015) American’s Languages: Challenges and Promise. American Councils for International Education, as cited by Friedman, A. America’s Lacking Language Skills in The Atlantic. 4. Cutshall, S. (2012) More Than a Decade of Standards: Integrating “Communication” in Your Language Instruction. ACTFL: The Language Educator 5. Bertin, J. C., Grave, P., & Narcy-Combes, J. P. (2010). Second language distance learning and teaching: Theoretical perspectives and didactic ergonomics. Hershey, PA: IGI Global. 6. Carrier, M., Damerow, R. M., & Bailey, K. M. (2017). Digital language learning and teaching: Research, theory, and practice. New York: Routledge. 7. Canagarajah, S. (2021) Diversifying academic communication in anti-racist scholarship: The value of a translingual orientation, Ethnicities 8. Norton Peirce, B. (1995) Social Identity, Investment, and Language Learning. TESOL Quarterly 9. Byram, Michael & Wagner, Manuela. (2018). Making a difference: Language teaching for intercultural and international dialogue. Foreign Language Annals. 51. 10.1111/flan.12319. 10. Macedo, D. (2019) Decolonizing foreign language education: the misteaching of English and other colonial languages. New York: Routledge. At the end of three disrupted years, it’s important for the final experiences of the academic year to recognize your community’s resilience, and to look towards renewal with optimism. That’s why we asked members of the Association of Academic Leaders to tell us what they’re working on to ensure a strong finish to the school year.

|

Don't miss our weekly blog posts by joining our newsletter mailing list below:AuthorsBrad Rathgeber (he/him/his) Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed